Inside every storage structure is an invisible battle between “good” and “bad” microorganisms. If the good guys win, the prize is tons of nutrient-rich silage. If the bad guys win, there may be significant dry matter (DM) and nutrient losses, excessive spoilage, feed refusals, low animal performance or even poor animal health and reproduction. We really need the good guys to win. Each year, we consult with livestock producers to help them tip the balance in favor of more available, more nutritious feedstuffs. It can make all the difference in an operation’s overall profitability. What’s more, many of the recommendations we make are not expensive or time consuming – and they certainly pay back.

What are your challenges?

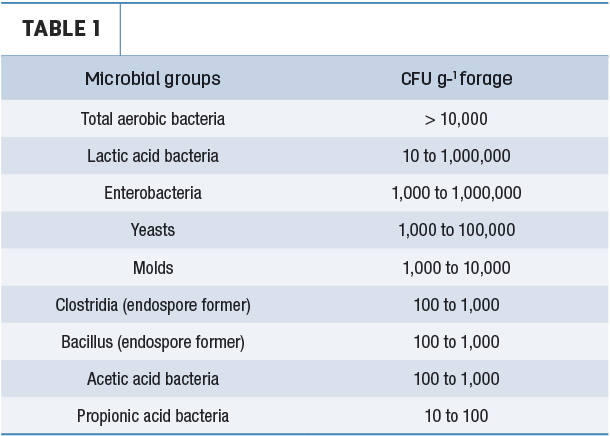

First, it’s helpful to understand what we’re battling. There is a wide range of naturally occurring microbes in standing crop plants (Table 1).

They vary in both type (bacteria, yeasts and molds), family (e.g., lactobacillaceae – a lactic acid bacteria), specific species (e.g., Lactobacillus buchneri), individual strains (e.g., L. buchneri NCIMB 40788) and numbers. The microbes are influenced by several factors, including:

- Manure and tillage practices

- Weather

- Stage of maturity of the crop

- Mowing practices

- Field wilting times

Microbes are further influenced by the ensiling process, which includes the ensiling structure, use of inoculant, speed of filling and covering/sealing. We will discuss this more in an upcoming article.

Plant respiration – and growth and activity of aerobic bacteria while oxygen is present through the forage mass in the ensiling structure – causes nutrient losses and prevents a rapid pH drop, in addition to producing heat. This is why speed, packing efficacy and sealing are important silage management practices.

Some unfavorable anaerobic microbes also can be present, which can pose a greater problem in competing with natural lactic acid bacteria (LAB) – good silage microorganisms – for dominance during fermentation, especially if there has been prolonged air exposure, resulting in the depletion of sugars to drive lactic fermentation. The negative competitors usually include enterobacteria – including coliforms – clostridia, yeasts and molds.

Important microbes to help ensure a good ensiling fermentation are LAB. Specifically, homolactic acid bacteria, which rapidly – and only – produce lactic acid from the sugars predominant in ensiled crops. The strongest of the fermentation acids, lactic acid production helps to drop pH quickly and stabilizes the forage crop by creating a low-pH environment that doesn’t allow mold and yeast to grow.

Unfortunately, these microbes are only present in very low numbers in pre-harvest crops. Therefore, addition of a research-proven inoculant is recommended. However, inoculants aren’t a magic bullet for producers to positively influence the microbial war during ensiling. We also have tried-and-true management practices that will help your loyal inoculant army prevail in the battle for your ensiled crop.

Manure application

Manure is a valuable nutrient source on livestock operations, since it recycles nutrients and helps sustainability. Yet, unsurprisingly, it can also harbor pathogens, such as E. coli and clostridia, that can negatively affect silage fermentation and feeding performance. Ideally, there should be a 28- to 32-day hay cutting interval from manure application to forage harvest. This is a common practice to reduce the risk of enterobacterial challenges in the resulting silage.

Cutting it too close to the last manure application can set the stage for enterobacteria and/or clostridia, which can compete with LAB in silage fermentation. Clostridia are also naturally occurring in soil, which means these fermentations can occur even when the manure application timing is on track, hence the importance of soil inclusion, indicated by ash in the silage analysis. Weather oftentimes doesn’t cooperate, and dry periods immediately after applications can allow enterobacteria to persist into the harvest window because they are attached to the silage crop.

Plant damage in the field

Drought, flooding and pest damage can all stress and damage plants in the field. Unfortunately, there are no strategies for preventing Mother Nature. Our best recommendation is to understand the potential effects and enact mitigation strategies, especially insect and disease control, where possible.

Crops damaged by any weather event – from flooding to hail or drought – are more prone to mold infestation and subsequent toxin production. Once you see mold growth in silage, a lot of the crop’s digestible nutrients may have already been used by yeasts, which grow first and cause heating. Some of these molds may produce mycotoxins, which can reduce production, affect herd health and fertility, and even be a food safety hazard.

To help minimize spoilage in silage, producers can use forage inoculants proven to prevent growth of specific spoilage organisms and focus on good management practices. Fast filling, effective packing and covering and sealing silage helps reduce oxygen exposure, protects it from the elements and further decreases the opportunity for spoilage.

Mowing practices

The drive to get the most out of your field can often end up in a trade-off with potentially lower digestibility and/or bad fermentations that result in waste later when spoilage occurs. Setting the mowing height too low can “scalp” the field and contaminate forage with soil or crop debris. Specific settings also can create a vacuum effect that brings soil into the forage, even when the height is correctly set. The practice of merging several windrows together can risk bringing in additional soil as well. Work with your equipment manufacturer’s representative to determine the correct settings for the specific crop.

Soil harbors a wide range of undesirable microorganisms, particularly clostridial spores. Therefore, if the forage to be ensiled – especially those that tend to be cut closer to the ground – contains great amounts of soil particles, the risk of microbial contamination and a bad fermentation outcome increase. Look for a future article in this publication that covers the possible animal production and health effects in greater detail. Level of soil contamination can be estimated in the forage analysis results as ash. (As reference, the internal content of ash in corn, grasses and legume plants is approximately 4%, 7% and 10% on DM basis, respectively.

Watch where you unload

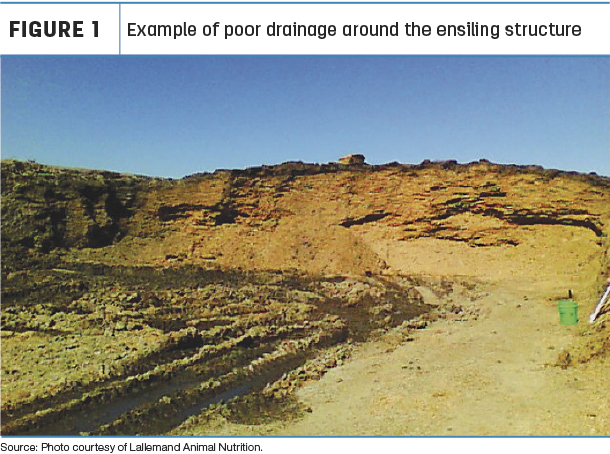

Ash contamination also can sneak in during the filling process. Misjudging pile size or building space can often mean forage is dumped on the ground. Inevitability, this requires scraping a tractor scoop on the ground to retrieve the forage, except now, you’re also getting a healthy dose of soil contamination and bad microbes, too. Poor drainage around the silo, especially by the feeding face, exacerbates this issue (Figure 1).

It is not expensive to keep a log of key metrics, like ash content in the forage analysis, feed intake and silage stability in the feedbunk. Yet these measurements can help determine if additional investments in space, concrete or packing are justified.

Add an inoculant

Simply achieving a fast initial fermentation to get the silage to a low, stable pH can help address a lot of challenges. Aerobic organisms are stifled and can no longer eat up your silage’s valuable nutrients, and nasty anaerobic bacteria like clostridia and enterobacteria are overwhelmed. In addition, some inoculants contain high-activity enzymes that provide additional sugars for LAB during active fermentation and also help break down plant fiber, which can improve fiber digestibility and feed utilization.

During feedout and for more significant challenges – including excessive spoilage losses, unstable silage and suboptimal harvest conditions – it is recommended that a combination inoculant including L. buchneri NCIMB 40788 be applied at 400,000 colony-forming units (CFU) per gram of silage, which has been uniquely reviewed by the FDA and allowed to claim consistent improvement in aerobic stability. The calculations on inoculant investment, spread over the cost per head per day, are easily justified by the return on investment provided by reputable, research-proven products.

Small changes add up

The forage portion of your ration is one of your most valuable assets: just compare the cost of your silage(s) for the year with the cost of other feed inputs for the year. Increasing the amount produced, or buying supplemental feeds, to make up for losses isn’t always a strategy that pencils out. Reducing your DM losses by just a few points can make a big difference in your operation’s bottom line – and we can do a lot better than that.

This is the first in a three-part series on silage hygiene. Subsequent articles will address management strategies during ensiling and animal health and will appear in Progressive Dairy.