Many of these stands were planted by the producer’s father or grandfather decades earlier, so the seemingly sudden stand loss has been surprising to them. Growers wonder what has changed and how they can rescue their fescue.

Like most natural phenomenon, reduced performance of tall fescue can be the result of many factors. Some of these factors interact with one another, thus causing the problem to be worse or the decline more rapid. Many environmental and management factors have changed over the course of a generation.

Weather extremes are definitely a contributing factor. Most farmers agree that the weather in the past 10 years has been more extreme than in any other 10-year span they can remember. Extreme drought and epic flooding, often within weeks of one another, have caused severe stress on tall fescue stands in many areas. Climate change has certainly played a role, but there have been significant management changes over the past 20 years that may be equally important contributors to these issues.

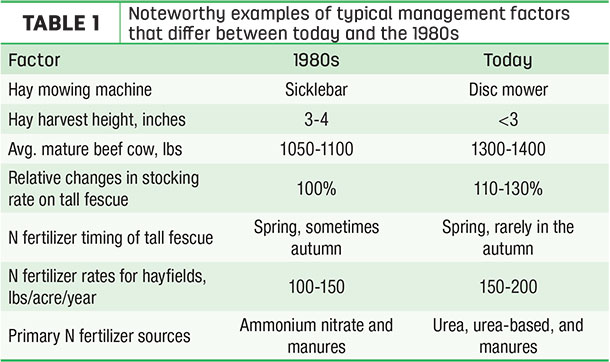

Some of these management differences are summarized in Table 1. Chief among these management factors has been a change in how we harvest and graze tall fescue stands. Hay cutting equipment in 2017 is much more efficient at harvesting every blade of grass in the field, often resulting in no residual leaf area and stubble heights less than 3 inches.

Similar increases in defoliation have occurred in pastures as well. The average beef cow weighed 1,050 pounds in 1975, but the current average is closer to 1,350 pounds. Since many producers still run about the same number of cattle to the acre that their father and grandfather ran, the effective stocking rate is about 30 percent greater than it was only a few decades ago. By leaving less green leaf area in the hayfield and increasing the grazing pressure, it should be no surprise that tall fescue stand loss is occurring.

Other changes that have occurred over the past few years are in nitrogen (N) management, including the timing of application, the rate applied and the primary form of N fertilizer that is used. This is relevant to the discussion because N dynamics in the tall fescue plant affect how “bunchy” this bunchgrass will be within the sward. Moderate N rates result in optimal carbohydrate concentrations in individual tillers, which causes the plant to put on more tillers. As a result, tall fescue spreads out along the soil surface and creates more yield.

Most growers will apply fertilizer to fescue in the spring, but autumn fertilizer applications can be just as important for high yields because it stimulates more tillering. Of course, fertilization should be based on soil test recommendations, but not all of that fertilizer needs to go out in the spring. To optimize tillering, provide nitrogen at a rate of 30 to 50 pounds N per acre and 50 to 60 percent of the year’s total recommendation of potassium about six to eight weeks prior to the first frost date. Fertilizing at this point in late summer or early autumn can substantially improve tiller density going into the winter. Fescue stands fertilized in this way may capture more sunlight in the cool season, build carbohydrate reserves and have the capacity to grow faster during spring green up.

Over-fertilizing or poor timing of N application can also have an impact. Research in Virginia from back in the 1960s showed that fertilizing tall fescue immediately after it has been cut closely may actually have a temporarily negative impact on its regrowth rate. Work in Georgia during the 1980s showed that when tall fescue forage was clipped in such a way that no green leaf area remained, N rates greater than 100 pounds N per acre resulted in the suppression of carbohydrate concentration in individual tillers for a longer period of time. This resulted in fewer new tillers being formed and a faster decline in tiller density. Consequently, the fescue will have more gaps in the stand and more opportunities for weeds to get established, all of which can result in rapid stand loss. Thus, the key is to spoon-feed tall fescue with several small applications of 30 to 60 pounds N per acre rather than putting too much on at one time.

Though the weather has gotten more extreme in the past few decades, our management has been a primary factor for stand loss in tall fescue. The fundamentals of how to keep a thick stand of tall fescue have not changed. Careful attention should be paid to how management changes influence tiller density. ![]()

-

Dennis Hancock

- Associate Professor and Extension Forage Agronomist

- University of Georgia

- Email Dennis Hancock

PHOTO: Pressure from higher seasonal temperatures, while affecting fescue stands, is not their greatest threat. Many management factors combine to increase stress on stands, and only management can fix those pressures. Photo by Dennis Hancock.