A fungus called Phymatotrichopsis omnivora infects the plant and leads to diseased plants wilting and rapidly dying in the mid- to late-summer months. Quickly, the fungus can spread to surrounding plants.

Carolyn Young, Ph.D., associate professor at the Noble Research Institute, has studied this fungus and how it interacts with the plant for the past few years.

“It’s a problem in a small part of the U.S.,” Young says, “but it is a big problem for those who have to experience it.”

The pathogen is associated with basic, high-calcareous soils, which makes the disease prevalent in southern Oklahoma and Texas, but it also exists in other parts of the southwestern U.S. and Mexico.

Causes

Despite the name of the disease, cotton root rot does not originate in cotton but from the fungus Phymatotrichopsis omnivora. This fungus is soil-borne and dangerous to a wide-range of dicotyledon crops (plants with two leaves at germination) and commercial crops including pecan, cotton and alfalfa.

This fungus does not affect monocots. Phymatotrichopsis omnivora produces scletoria (a fungal resting structure equivalent in size to alfalfa seed), allowing the pathogen to remain dormant for long periods of time, which makes the pathogen extremely difficult to eradicate from a field, Young says.

“When the disease starts, you will see a very dramatic sudden ring of dead plants,” Young says. “That ring of dead plants will just keep spreading and spreading throughout the growing season of alfalfa.”

When temperatures rise above 82.4ºF, the fungus is no longer in a dormant state and is actively spreading throughout the soil. Young says this typically begins to happen in mid-June, but in the 2018 growing season in Ardmore, Oklahoma, it began in late May.

Effects

Cotton root rot threatens the longevity of the alfalfa plant and can drastically shorten the stand life of a field planted.

“Typically, we like to have alfalfa fields last between five and seven years,” says James Rogers, agronomist at the Noble Research Institute. “In areas just north of us, fields average about seven years, but in our region the fields affected by cotton root rot only last about three years.”

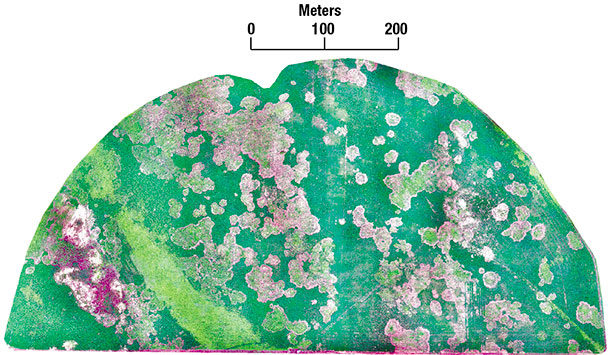

Each growing season, the disease spreads and kills a larger area of live plants, leading to loss in production and an increase in bare grounds in the field, allowing encroachment of weeds. Young says the area can spread 3 to 5 yards each growing season.

“What we saw from June 2014 to October 2015 is the area under cultivation went from 13.7 hectares [38.8 acres] to 9.4 hectares [23.2 acres],” Young says. “The area of bare ground increased from 5.8 hectares [14.3 acres] to 10.1 hectares [25 acres].”

The loss of quality alfalfa has caused several producers in the area to stop growing alfalfa entirely.

“The seed cost is very high, and we have a lot of producers who just avoid growing alfalfa because of cotton root rot,” Rogers says, “which is a shame, as alfalfa is an excellent forage.”

Avoiding the pathogen

Management options for producers experiencing cotton root rot are very limited. Crop rotation involving only monocots (grasses and wheat) is the most popular management practice in place now, says Young.

There is a fungicide application now available for cotton to help combat the spread of the fungus and improve production, but it has not yet been labeled for use in alfalfa. Young says this has the potential to change in the next few years.

Steven Thompson, an alfalfa farmer in south-central Oklahoma, has experienced cotton root rot in the past few years. His 25 acres of alfalfa is in its third year of stand life, and it may be the last. Thompson says he planted the field with oats four years ago and planted alfalfa the following year.

Since then, approximately 30 percent of the alfalfa planted has perished because of cotton root rot. The disease has impacted his production so drastically he will be faced with the decision to rotate the field at the end of the year, about three years sooner than expected.

“I hope to get at least one more year out of it,” Thompson says. “I will just have to see how much of it has been killed off by that time.”

Thompson says the cost of production after getting only three years out of a stand versus six to eight years is relatively high when compared to other places.

Producers who are affected and the research team at the Noble Research Institute are actively working toward finding a solution for cotton root rot in the coming years.

“It’s a fun pathogen to study, but sometimes it keeps me up at night,” Young says. ![]()

PHOTO: This aerial image of an alfalfa field at Noble Research Institute’s Red River Farm shows the progression of cotton root rot. Image courtesy of Noble Research Institute.