For states such as California, which generally see very little rainfall across most of the state, drought is a major concern for those in the agriculture industry.

Alfalfa, which has a long growing season and covers between 900,000 and a million acres in California alone, is responsible for consuming 20 percent of applied water used in the agriculture industry in spite of its good water use efficiency (WUE).

Due to its deep-root system, which enables it to access water that might not be available to other crops, alfalfa is surprisingly drought tolerant as compared with other crops.

Additionally, when the water has been depleted from the soil, alfalfa will assume what is known as a “drought-induced dormancy” where the plant ceases to grow. However, the plant can survive long periods without water. As a result, mature alfalfa can tolerate some flexibility in the amount of water it receives.

In the study, three basic plans were formed for growing alfalfa in a drought:

- Reduce irrigated acreage of alfalfa (cease irrigating some fields and fully irrigate others).

- Fully irrigate early cuttings then cease irrigation on all fields.

- Deficit irrigate the entire acreage during the crop season (fewer irrigations or less water per irrigation) so that less than full evapotranspiration (ET) is applied.

While each plan has its pros and cons, there are several questions the grower should consider when devising a plan of action.

Is water available for the entire season? Or, in a water-short year, is there only water available in the spring and then the water runs out? Or is there water available season-long but at a reduced delivery rate?

If there is ample water available in the spring, option two is likely the best choice. This conclusion was reached on the basis that in the intermountain area of California, roughly 75 percent of the annual alfalfa production occurs by mid-July. The Central Valley sees a similar phenomenon where 64 percent of the annual production occurs by that time.

Consequently, water efficiency is better in the spring than other times of the year. Not only that, but the quality of the forage is generally highest in the spring. The result is that sufficient irrigation in the spring will produce a better return than it would in the summer or fall.

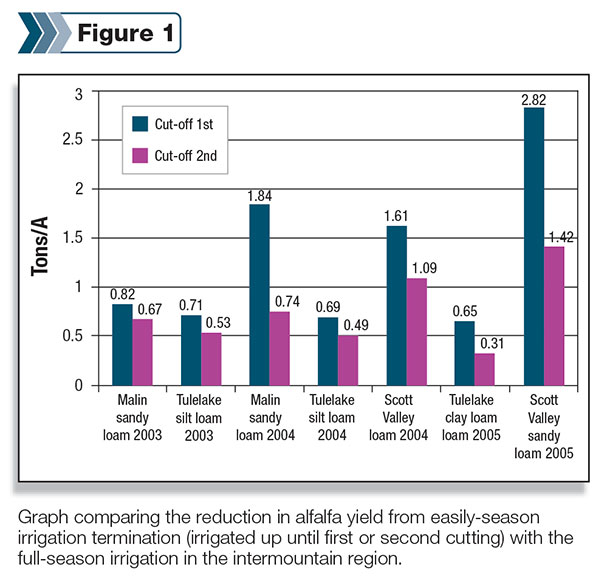

Keeping this in mind, Orloff, Putnam and Hanson conducted several trials in the intermountain area and Sacramento Valley of California. In the intermountain studies, a normal full-season irrigation was compared with cutting off irrigation before the first cutting and with cutting off irrigation before the second cutting.

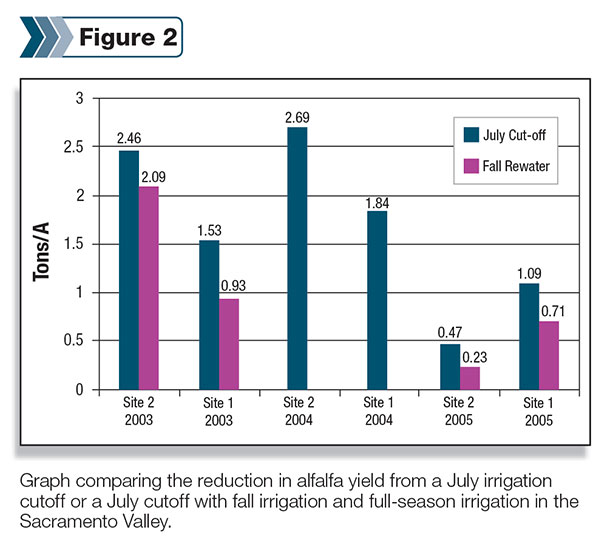

In the Sacramento Valley, on the other hand, full-season irrigation was compared to an early summer cutoff or an early summer cutoff with fall irrigation. In every location experiencing early irrigation cutoff, alfalfa yield was reduced every year.

The amount it was reduced, however, was site specific and depended heavily on the soil type and the depth to groundwater.

In the intermountain region, the yield reduction with the early irrigation cutoff was between 0.65 and 2.82 tons per acre while the yield reduction when irrigation was ceased before the second cutting was lower, ranging from 0.31 to 1.42.

Alfalfa planted in an organic clay loam soil and a high water table experienced the least yield reduction.

The trials in the Sacramento Valley showed similar results with a yield reduction ranging from 0.47 to 2.69, which was highly dependent on the soil type and water content.

Re-watering in the fall had little effect in the seasonal yield reduction. In fact, in most cases, only about half a ton of the annual yield was saved with a fall irrigation as compared with the July cutoff with no subsequent irrigation.

This is due to the recovery period needed by the alfalfa plant after it has experienced a drought. During this time, the plant grows very little. Another contributing factor is the higher amount of water required to seal the cracks and refill the soil profile.

It is, therefore, generally not recommended that producers apply a fall irrigation after a summer drought unless the water shortage has ended and irrigation water is plentiful.

Although it is no shock that the yield would be reduced after a drought, what may be a little more surprising is that in these trials, the alfalfa showed no difference in stand or yield in the following year. It did not matter if it had been fully irrigated all season or had experienced drought at some point.

The stand was assessed using visual stand ratings and counts of the number of stems per unit area.

Since this is highly dependent on environment, length of growing season, soil type, water table depth and possibly even alfalfa variety, the results of this study may not be true of every area.

Due to its shorter growing season and cooler temperatures, alfalfa in the intermountain area was less likely to experience adverse effects than it might in other areas of California. The intermountain region has limited dryland alfalfa production, indicating that alfalfa can survive an extended dry period in that climate.

However, it appears that it must become well established or reach a critical size before it is able to do so. Otherwise, stand loss may be noted.

Due to its long growing season and high temperatures, the low desert of California experiences the most loss. It is best in medium textured soils, but fairs poorly on sandy or very heavy cracking clay soils.

This may be due to the hydraulic conductivity of the soils or the speed at which water can move through the soil. The result is that water cannot move upward from the perched water table fast enough to sufficiently hydrate the plant in some soil types.

Since no irrigation application method is completely uniform, producers will apply more water than used during evapotranspiration to ensure that every part of the field receives an adequate amount. Due to percolation, this technique causes diminishing returns in terms of yield.

Water that moves past the root zone has little effect on yield. Normally, this technique is accepted and recommended to ensure all areas of the field get sufficient water, but in drought situations, this may not be the best course of action.

In such cases, water application closer to the ET value will improve water use efficiency, even if it leaves a few dry spots in the field. FG

Summarized by Progressive Forage Grower staff from “Deficit Irrigation of Alfalfa during Drought” by Steve Orloff, farm advisor, UC Cooperative Extension, Yrek; Dan Putnam, alfalfa and forage specialist, UC Davis; and Blaine Hanson, irrigation specialist emeritus, UC Davis.