The company sought out novel bacterial strains with specific animal nutrition-enhancing properties that could be used as silage inoculants. This article will explain the science to help you make the right choices about using fiber technology inoculants in your ration.

In 2007, a scientific paper was published regarding the influence of inoculating forage with bacterial strains that produce ferulate esterases during the ensiling process and ultimately impact improved ruminal degradation of fiber. Three such products are commercially available.

Fiber-technology forage additives in action

The mechanism of action of fiber-technology (FT) forage additives is to alter the cell wall complex by enzymatic “decoupling” of the chemical ester bond that links cell wall polysaccharides to indigestible lignin. Since lignin is not destroyed, the fiber fragility (effective fiber) is similar between normal silages and those inoculated with FT inoculants. Dry matter intake is not significantly increased, as is the case with reduced-lignin crops like BMR corn silage or sorghum.

Two added-value, cost-saving opportunities exist when feeding FT-treated silages to dairy cows:

-

Opportunity to lower corn grain supplementation

- The lignin decoupling process changes what normally would be recognized by rumen microbes as slowly released carbohydrate – primarily neutral detergent fiber (NDF) – to digest like fast-release carbohydrate, similar to that of starch and sugars. Knowing this, researchers developed feeding guidelines suggesting that supplemental energy from feedstuffs like corn grain can be lowered in the diet. The difference is filled with more FT corn silage inclusions, which ultimately produces a higher forage-based ration that is healthier for the dairy cow.

-

Opportunity to lower protein supplementation

- With FT-treated silage, fiber digestion rates become faster, thereby increasing the amount of fiber rumen microbes can utilize during rumen residence times. The net result is increased microbial protein production within the rumen, which the cow can utilize to meet protein requirements for maintenance, growth, reproduction and milk production. The FT inoculant benefit of increased fiber digestibility in the rumen and higher rumen microbial biomass populations (bypass protein source) provides an opportunity for fine-tuning of the diet by removing some protein supplement.

Alternative gas production digestion: Fermentrics testing

Conventional near-infrared (NIR), or wet chemistry, in vitro neutral detergent fiber digestibility (NDFD) laboratory offerings do not have the sensitivity to predict the digestion rate increases that have been validated with performance cattle studies. This is because in vitro NDFD methodologies do not detect the decoupling effect of NDF, in contrast to research studies that used live-animal in situ digestion models that do pick up increased NDFD. Industry experts developed an alternative gas-digestion method that helps explain and quantify the added value of FT technology.

One such gas-production digestion technique is Fermentrics, available commercially through Dairyland Laboratories, Arcadia, Wisconsin. The test determines kinetic rates of digestion (Kd) for fast- and slow-released carbohydrates. The reports graphically illustrate the rate of digestion of the “fast carbohydrate pool” and the “slow carbohydrate pool.”

Fermentrics allows for the calculation of microbial biomass production (MBP) during rumen and post-rumen residence times. The data generated proves extremely helpful in quantifying and managing the associative effects of FT-treated silage with other various dietary ingredients. The Fermentrics method measures MBP directly by analyzing the substrate that remains after a 48-hour incubation with an NDF analysis (without amylase or sodium sulfite). The difference between the weight of the substrate before and after NDF analysis is the microbial biomass.

The MBP value can then be used to calculate production of rumen microbial protein (MP). For example, rumen models such as the Cornell Net Carbohydrate-Protein System (CNCPS) show that a 1,600-pound Holstein cow milking 80 pounds of milk per day requires about 2,700 grams of MP per day. FT silages fed at 50 pounds silage per day show an increase of 200 to 300 grams MP on Fermentrics reports, which translates into about 0.5 to 0.75 pounds lower protein supplementation in the diet. This is in addition to a potential 1 to 2 pound reduction of corn meal in the ration. These amounts can be adjusted up or down based on higher or lower ration-inclusion rates of FT silage.

How the nutritionist can balance rations to capture the FT-silage value

The following guidelines, written by nutritionists, use rumen-modeling programs that allow for changing silage digestion rates.

- Models such as the CNCPS allow for modifying Kd value of the B-pool carbohydrate fractions of feedstuffs: B1 (starch), B2 (soluble fiber) and B3 (NDF). Rather than using book values, nutritionists can replace existing book value rates in the model with measured Kd values from Fermentrics. The model can then be used to fine-tune diets and potentially reduce concentrate and protein supplementation (depending upon the digestion kinetics of the previous years’ forage crops) by adjusting the rates based on the effect of FT inoculants on the B-pool carbohydrates.

- Running Fermentrics tests on silage samplings two or three times during the silage feedout season is advised because the various Kd rate values may be higher with longer silage storage times.

- Several forage-testing laboratories report a B3 Kd value calculated from NDF, lignin and single time-point NDFD values. The calculation is based on the Van Amburgh Rate Calculator developed at Cornell University. A newer calculation used undegradable NDF (uNDF) values at 30-, 120- and 240-hour time points. Regardless of which method is used, the drawback of adjusting only the B3 Kd value is that it misses the increased B1 and B2 Kd rates that are the result of FT inoculation.

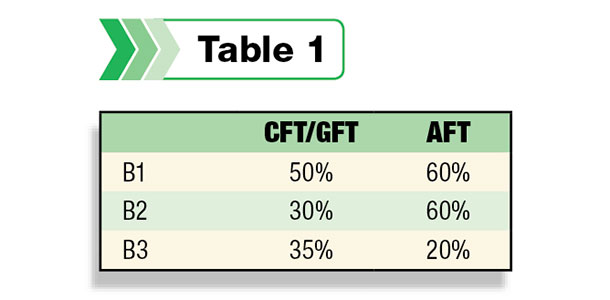

- Fermentrics analyses summaries based on hundreds of samples have shown that the B-pool carbohydrate rates are increased, on average, by the amount shown in Table 1. (For example, the FT corn silage book value B3 rate of 3.4 percent per hour should be increased by 35 percent to 4.6 percent per hour.) Adjusting book values upward by these percentages is a possible approach, but only if the feed library B-pool rates approximate the true rates of the forage (which is unlikely given the huge growing environmental impact on carbohydrate digestion rates).

The following guidelines, also from nutritionists, use balancing software programs that don’t allow for changing silage digestion rates during ration formulation.

- Cows should be monitored and their diet gradually modified to account for the changes in rate and extent of fiber digestibility in FT-silages compared with old-crop silages. This is best accomplished by monitoring feed intake, milk production, milk components and manure consistency. Depending on growing-condition influence, new-crop silage treated with FT inoculant may result in higher, similar or lower digestibility compared with old-crop.

- There is no problem with feeding FT-treated silages several weeks after ensiling, but the full benefit of the enzyme activity will not be realized until the silage has fermented for 60 days.

- A starting point for removing concentrate from FT-treated silages is to start with removal of 1 to 2 pounds of corn meal (as fed), followed by about 0.5 pounds of 44 percent crude protein meal (as fed). These amounts can be adjusted up or down based on higher or lower ration inclusion rates of FT silage.

- Increased inclusion rate of FT-treated corn or cereal silages is a benefit for meeting total daily starch requirements. Adjustments will also be necessary for increased starch digestibility over time in storage between new-crop and old-crop feeds.

Follow-up with herds expressing production problems when fed FT silage typically reveals borderline levels for starch content or physically effective fiber. Fat depression and acidosis issues are usually resolved quickly (and feed costs lowered) by reducing grain (especially highly ruminally fermentable high-moisture corn), increasing forage inclusion rates (and effective fiber) or adding coproducts that deliver sources of soluble fiber. FG

-

Bill Seglar

- Senior Nutritionist

- DuPont Pioneer

- Email Bill Seglar

PHOTOS: Photos by FG staff.