Forage sorghum hybrids yield more dry matter than sorghum-sudangrass, produce better-quality forage and are used for silage or greenchop. Grain-bearing forage sorghum hybrids are generally used for silage production because they produce a palatable growth in late-season pastures.

Forage sorghums have the potential to produce large amounts of nutritious forage during the summer months, and their inherent versatility fits into many different growing or livestock operations.

Sorghum hybrids targeted for silage are good matches for dryland and limited irrigation situations. Significant drought tolerance is a key benefit of forage sorghums.

They can also be used in an emergency as a late-planted crop to replace a primary crop damaged by wind, hail or drought early in the growing season. Forage sorghums offer growers a diverse range of management options to match their production needs.

Hybrid options

Forage sorghum hybrids are similar to grain sorghums, but they are taller, leafier and may produce less grain. They range from 6 to 14 feet in height, with stalks that are usually large in diameter and may contain a sweet juice.

Seed heads may have a more open panicle with smaller seeds than grain sorghum. Milking and feeding trials show that feeding forage sorghum and corn silage both result in the same milk production and cattle gain rates. One distinct advantage of forage sorghum is that it requires significantly less water than corn.

Forage sorghum hybrids offer a wide range of yield and nutritive values – the central factors in determining which variety to plant. If the silage will be fed to lactating cows, quality considerations will probably be the dominant factor.

However, in the case of dry cows or feedlots, yield may outweigh quality, particularly if silage acres are limited. Forage sorghum hybrids display a broader range of grain, leaf and stem digestibility than corn silage options.

Although forage sorghum yield is one factor, nutritive value should be carefully considered as a strategy toward consistent forage feeding.

The greater energy value and digestibility per pound of corn silage remains a key reason for selecting it over forage sorghum.

Currently, growers who plant corn can be more confident in the consistency of its nutritive value at harvest compared to forage sorghum – primarily due to the wide variation in nutritive value of forage sorghum cultivars.

Continuous corn breeding selection for greater fiber digestibility, higher starch content and higher drought tolerance could move the balance even further toward corn.

Increasing forage sorghum nutritive value with BMR genes

The BMR mutation that affects fiber concentration and increases digestibility has been used to enhance the nutritive values of corn and forage sorghum.

Phenotypic changes on BMR sorghum plants are visible in a brown pigmentation in the mid-rib of the leaf, stem, pith and immature panicle branches. In all cases, the brown coloration is found in the vascular tissue, which is linked to indigestible tissue.

However, it’s incorrect to generalize that all BMR forage sorghums are better than conventional forage sorghums; selection should be based on performance by individual cultivars.

The phenotypic traits of forage sorghum cultivars vary, and the wide ranges in plant height, dry matter content and grain yield contribute to marked differences in nutritional value among sorghum cultivars.

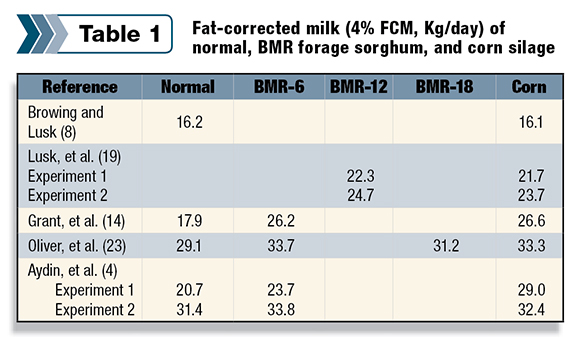

Table 1 summarizes documentation that forage sorghum BMR cultivars can be a substitute for corn silage in lactating dairy cow rations without affecting milk yield.

However, the 20 percent or greater reduction in dry matter yield of forage sorghum BMR compared with corn makes it difficult for growers to prefer BMR forage sorghum over corn.

For those facing a declining water supply, forage sorghum will remain a good option compared to corn for silage production.

Relative feeding value

Relative feeding values are used to compare forage sorghum types to corn silage. In general, forage sorghums will have 80 to 90 percent of the energy value of corn silage per unit of dry matter.

Sorghum-sudangrass hybrids usually have 65 to 75 percent of the value of corn silage. The inherited wisdom is that a high grain yield is necessary for forage sorghum to produce high-quality forage. While this tends to be true with conventional forage sorghums, it’s not true with BMR hybrids.

Research has shown that BMR hybrids can have a low percentage of grain in the silage but be high in nutrition.

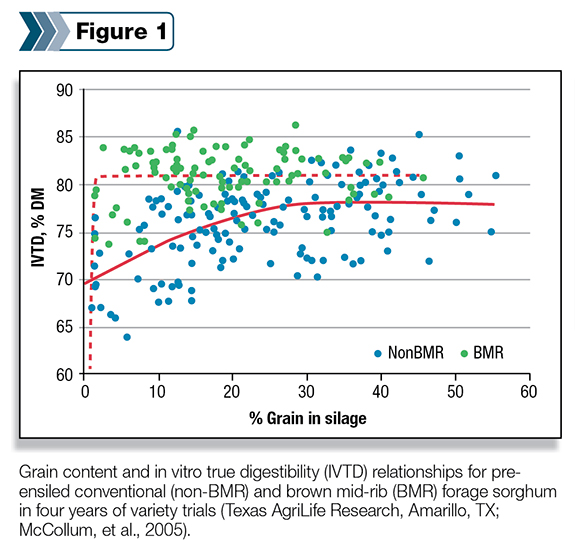

In Figure 1, the percentage of grain content in pre-ensiled non-BMR and BMR forage sorghum was compared to its in-vitro true digestibility (IVTD).

Conventional forage sorghums’ IVTD increased quadratically and plateaued at 78.0 percent when the silage was 34.5 percent grain

. In contrast, the IVTD of BMR forage sorghums plateaued at 80.8 percent when grain content was only 2.0 percent of the total weight (Figure 1).

Two main types of forage sorghum hybrids, BMR and non-BMR, are most often used for silage production. BMR hybrids contain less lignin than non-BMR hybrids.

Lowering the lignin content increases the overall digestibility and thus improves nutritive values.

The disadvantage of the BMR hybrids is that lodging can be a more significant issue, particularly if harvest is delayed past the optimum stage.

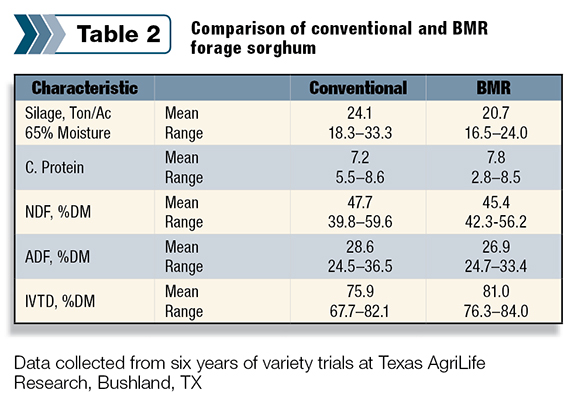

The average yield and nutritional characteristics for 35 BMR and 22 non-BMR hybrids in a trial conducted in 2011 at the Texas AgriLife Research field lab are reported in Table 2.

Ensiling considerations

Though there are some differences, forage sorghum silage requires largely the same management practices as corn silage: Determine proper moisture content and length of cut, pack properly, and avoid contaminants such as soil and cover to prevent exposure to air and moisture.

1.Maturity and moisture: Forage sorghum should be harvested when the whole-plant moisture content is between 63 and 68 percent.

In grain-producing forage sorghums, the correct moisture content is generally present when the grain has reached the soft-dough stage.

This stage occurs after the liquid inside the grain has changed to a dough-like substance yet is still soft enough to be mashed between the fingers.

Do not delay silage harvest until the hard-dough stage because sorghum becomes progressively less digestible as it matures. Harvesting at the soft-dough stage and chopping it before the grain gets too hard will result in higher digestibility.

2.Length of cut: The correct length of cut is determined by the crop’s moisture content and its intended use. The ideal length for forage sorghum is three-eighths to one-half inch, according to Kansas State University data.

Longer cuts tend to cause packing problems, while finer cuts can create feeding problems in dairy cattle.

3. Forage preservation: Since sorghum silages tend to have a higher moisture content when chopped than other forages, growers should use a research-proven silage additive.

High-moisture content favors butyric acid-producing bacteria, which can result in foul-smelling, unpalatable feed and excessive dry matter loss.

The use of an inoculant will help minimize butyric acid production, reduce fermentation time and seepage, and produce higher-quality silage with less dry matter losses (trial data available upon request).

4.Toxicity potential in forage sorghum: Sorghums have the potential to be very toxic to animals. Producers should guard against prussic acid poisoning and nitrate toxicity (NO3-).

Prussic acid, or hydrocyanic acid (HCN), is formed from naturally occurring cyanogenic glucosides in the sorghum plant and is readily absorbed in the bloodstream, leading to respiratory problems and eventual death if high enough concentrations are consumed. In cases of prussic acid poisoning, the blood of animals appears cherry red.

Plant cell injuries from a variety of factors can raise HCN levels. HCN converts rapidly to a gas, so in most cases toxic levels are greatly reduced before ensiling during the chopping process. For this reason, HCN is seldom a problem in silage.

As a general rule, anything that suppresses or disrupts the growth of leaves relative to root absorption (i.e., drought, overcast days, frost, low temperatures, shading, herbicide damage, hail, disease) could contribute to increased levels of NO3- in the plant.

Excessive nitrogen fertilization may result in toxic forage as well, especially when combined with drought stress. As a general recommendation, feeding programs should be modified if silage contains more than 1,000 ppm of NO3-.

Waiting four days to one week after a stressful environmental condition (drought or frost) before chopping for silage or greenchop is recommended to help avoid high NO3- levels.

Drought or stressed silages that have not been inoculated should ferment a full three weeks before feeding. If the forage is inoculated with a reputable product, nitrate levels should be reduced by 40 to 50 percent in just a few days.

Ensiling forage sorghum with high NO3- concentration can produce lethal silo gas. The nitrous oxide decomposes to water and gases, including nitrogen oxide (colorless), nitrogen dioxide (NO2, reddish-brown color) and nitrogen tetraoxide (yellowish color).

This mixture is volatilized as a brownish gas that is heavier than air and lethal to humans and livestock. For this reason, care should be taken when a silage pit or bag is first opened in cases in which high NO3- levels are suspected.

High-nitrate feed should be limited in the animals’ diet, and it is always critical to check NO3- concentrations before feeding.

Keep all of these considerations in mind when feeding forage sorghum. FG