Nitrates in forages

The most common form of soil nitrogen utilized by forage plants is nitrate. Soil nitrate is taken up by the roots and rapidly converted to plant proteins in well-functioning plants. Much of this conversion happens in the plant leaves, so the nitrates have to travel up the stem to get to the leaves. This is extremely important to remember throughout this discussion.

So what happens in plants that aren’t functioning well? Nitrate comes into the plant night or day, rain or shine. High nitrates arise not from an increased supply from plant roots, but from a decrease in the rate of conversion to protein. The key to avoiding high nitrates in plants is to keep this conversion going as fast as possible.

To keep the conversion running at full speed, avoid situations that stress the plant. One example is drought stress, which reduces the ability of leaves to perform the conversion, but unless the drought is extreme, nitrates will still be entering the roots. Frost also damages leaves’ ability to convert. Extended cloudy weather slows the rate of conversion.

One interesting case we don’t often think of is hail damage. Extreme hail damage can result in a field full of stems that are taking up nitrates, but the leaves needed for the conversion process are simply gone. A management situation that can increase the risk of nitrate accumulation is the application of high rates of nitrogen (N) fertilization.

Heavy N fertilization coupled with any of the other stresses listed above increases the risk even more, especially for the first few days after fertilizing.

Here are some steps to reduce the dangers of nitrate toxicity in forages:

- Remember that stressed plants can accumulate nitrates.

- Not all forages have equal ability to accumulate nitrates. The sorghum family, corn and small grains have the highest potential for excessive nitrates; legumes are less susceptible.

- In any plant, nitrates are highest in the lower part of the stem. Increasing stubble height of stressed forages can reduce nitrate levels in the fed forage.

- Ensiling can lower nitrate levels in the forage somewhat. Making dry hay does not reduce the nitrate level very much.

Nitrates in ruminants

Nitrate poisoning is definitely an issue where an ounce of prevention truly is worth a pound of cure – maybe more. Let’s get to the bottom line early – once you have animals showing signs of nitrate poisoning, there isn’t a lot you can do. Methylene blue administered intravenously is the standard treatment.

In extreme cases, death can occur in as little as one hour. Symptoms can include tremors, rapid breathing, abortions and gray or brown mucous membranes.

However, planning ahead can really minimize the dangers of nitrate poisoning. The following can reduce susceptibility of animals to nitrate toxicity:

- Having animals in good body condition

- Ensuring animals are on a good mineral nutrition program

- Multiple feedings per day compared to one feeding

- Supplementing with feeds low in nitrates such as grain

- Incrementally increasing exposure to high-nitrate forages to increase animals’ tolerance

One of the wonders of the rumen is the ability of the microbes to combine carbohydrates and ammonia to make protein. To do this, the microbes have to convert the nitrate in forages to nitrite, and the nitrite is then converted to ammonia. This process is going on all the time in the rumen but the conversion of nitrate to nitrite is much faster than the conversion from nitrite to ammonia.

So if an animal consumes a huge amount of high-nitrate forage, a buildup of nitrite will occur as the animal converts all that nitrate to ammonia. This is important because nitrite is ten times more toxic than nitrate. Nitrite enters the blood and interferes with hemoglobin’s ability to bind oxygen. In other words, animals that die from nitrate poisoning die from lack of oxygen. That explains the classic symptoms of pale or gray mucous membranes and brown blood.

So in thinking about how to manage the risks of nitrate poisoning, we need to be cautious about any conditions that would overload the conversion process of plant nitrates to microbial ammonia. Slow and steady wins the race here for sure. Forage that is high in nitrates can be fed, but in small amounts combined with lower nitrate feed and in multiple feedings per day.

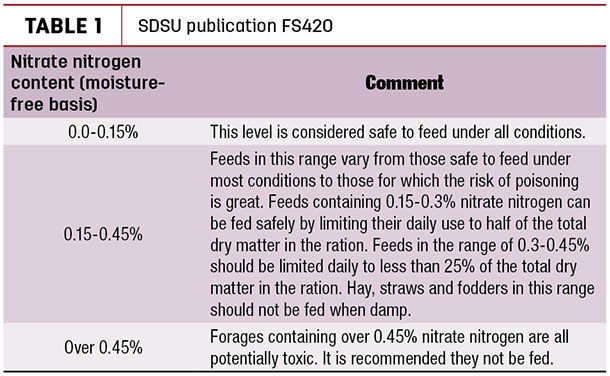

Table 1 (from a South Dakota State University publication) shows the ranges of nitrate in feed and in the fine print below discusses the conversion between several common expressions of nitrate that your lab may use.

Two final points worth mentioning are: First, test the livestock water. Any nitrates in the water count toward the total accumulation of nitrates in the animal. And second, remember that some weeds like kochia, pigweed and johnsongrass are notorious for nitrate accumulation. Field edges or overgrazed pastures where these plants make up a majority of the forage consumed can be troublesome.

As the summer heats up and plants and animals get stressed, it is wise to be concerned about nitrate toxicity, but this is a problem that can be successfully managed. Test any forage that is questionable in your mind. Many forage testing labs will test for nitrates in forages. Also, nitrate test kits for forage are widely available at farm supply stores.

If we observe and manage our forages and animals, the issue of nitrate toxicity does not have to be as dramatic as “nitrates, nitrites and dead cows.” ![]()

-

Chad Hale

- Research and Acquisitions Manager

- Byron Seeds

- Email Chad Hale