One of the largest costs of growing a forage is fertilizer. A ton of high-quality grass (dry matter) contains about 50 pounds of nitrogen, 18 pounds of phosphate equivalent and 60 pounds of potash. When you remove hay from the land, you must replace these nutrients to maintain production.

When that same ton of forage is consumed by the grazing animal, a high percentage of the fertilizer nutrients are excreted either as feces or urine. About 75 to 95 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium consumed are excreted, and the higher the nutrient levels in the forage, the lower the percent retention by the animal. Most soil tests will recommend a lower level of fertilizer nutrients for pastures than hayfields, but the credit given to the recycled nutrients is low.

So why are the excreted nutrients given so little credit? With continuous grazing, many of these nutrients will be deposited in areas where animals concentrate. Any time animals are allowed to loaf in the same areas day after day, soil nutrients will be harvested from all around the pasture and then deposited in places where they don’t do much good. According to work by Jim Gerrish, with continuous grazing it would take 27 years for every square yard of a pasture to receive a fecal pile while, with daily rotation, each square yard of pasture would receive a pile in two years.

Recent work with nutrient distribution on pasture-based livestock farms

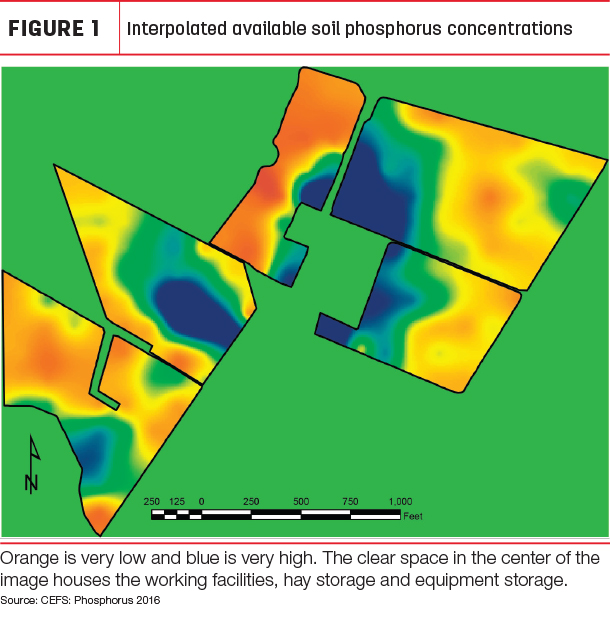

As part of a recent Conservation Innovation Grant project, we collaborated with Alan Franzluebbers and conducted spatial nutrient mapping on both public and private farms. The recent map from that same site is shown in Figure 1, and the various colors show available phosphorus levels, with orange being very low and blue being very high.

The high levels of concentration are close to the central working facilities and hay storage. When we mapped this same farm 20 years ago, the same pattern was visible – and since that time, we have been using adaptive grazing management with frequent rotation.

The high concentrations seen represent historical winter feeding areas, some of which are still used for feeding but others unused for 20 years. This shows once you have elevated phosphorus, it is likely to stay elevated a long time, even with changes in management. Maps from other farms show similar patterns, depending on historical management.

One of the novel things about our recent work is: We are also measuring indicators of “soil health” including carbon and soil test biological activity. In many cases (but not all), these indicators are closely related to the nutrients, especially in recently used feeding areas. Soil test biological activity as measured in Franzluebbers’ lab is a good predictor of future available nitrogen and is undoubtedly important in recycling of other nutrients.

Practical approaches to improve nutrient cycling

It is clear nutrient cycling is critical to the efficiency of pasture systems, and there are a number of things you can do to enhance the process. Ideally, you would start with a spatial distribution map of your farm, although this would be expensive. In our work, we used a 130-foot grid between samples, and thus a farm of 200 acres would require about 600 total samples.

You could use a less detailed grid to reduce the cost, but at some point you lose the detail on the land. While having that kind of a map can help you find “hot spots” and guide fertilizer application and routine sampling, there are many other things you can do to take advantage of nutrient cycling.

Building fertility in general on your farm is a critical first step in enhancing nutrient cycling. If uptake of nutrients by the plants is low due to low yield and low forage nutrient concentration, then there will be fewer nutrients to excrete back to the pasture. Some use of waste materials such as poultry litter, biosolids or compost can help you elevate phosphorus, potassium and micronutrients in a uniform way.

It is important for farmers to recognize all fertilizer inputs for what they are. Sometimes we hear “I don’t ever use fertilizer” while, in actuality, the farmer in question may be bringing nutrients on the farm from purchased hay, feed or waste nutrients. More and more livestock farmers are purchasing hay, and it is important to remember that is a source of fertilizer once it goes through a cow. That “fertilizer” can be dumped mostly in a central feeding area, or it can be distributed around the land.

Placement of shade and water are critical in getting good cycling of nutrients. Waterers and shade are especially good places to find nutrient hot spots, so making those more central in the pastures and making more total locations will help. Shade high in the landscape away from surface water and drinking tanks will help animals cool themselves and will lead to less concentration and thereby improved nutrient distribution.

As mentioned earlier, rotational grazing will be one of your best tools to get nutrients evenly distributed. The higher the stock density (pounds per acre at any one instant), the more uniform the manure distribution will be.

Another option is to change where cattle stay by using an easily portable mineral feeder. One of the issues with using a mineral feeder for this purpose is: Many are very difficult to move and thus fall into the realm of concentrating the cattle unintentionally. The “barrel and tire” model is the one I like best, and you can see a video on YouTube about how to construct it and can access a set of plans at our CEFS/Amazing Grazing webpage.

The final key to taking advantage of nutrient recycling is patience. You don’t go from a farm with low biological activity in soil and poorly distributed nutrients to a farm with healthy soil with strong nutrient cycling overnight. Getting the fertility up in general, implementing regular soil sampling, improving infrastructure (fencing, shade and water), learning better grazing management skills and other critical practices all take time.

As mentioned earlier, it will take several years to get feces and urine to impact every square yard of pasture, even if you use very good grazing management. Like with so many things in life, it is the combination of all your practices and time to let them work that lead to dramatically better pastures in the long run. ![]()

PHOTO 1: Strip-grazing concentrates impact on a small area, improving manure distribution.

PHOTO 2: A tire and barrel mineral feeder is easily moved around a pasture to improve nutrient distribution. Search “Amazing Grazing and CEFS” to see a set of plans for construction. Search “Cattle Mineral Feeder” on YouTube to see an instructional video. Photos provided by Matt Poore.

-

Matt Poore

- Livestock Commodity Coordinator and Ruminant Nutrition Specialist

- North Carolina State University Extension

- Email Matt Poore