Grazing management is the single-most important factor affecting the cost-effectiveness of the forage enterprise.

Grazing management will most notably improve efficiency in addition to (among many other advantages) recycling the fertilizer applied to the pasture, allowing greater utilization of legume species that may not tolerate continuous grazing and allowing for an extended grazing season.

Managed grazing improves efficiency

Take a moment to think about how much of the forage you grow will actually make it into the animal’s mouth.

Of the total forage produced, what percentage do your animals actually use? This percentage is referred to as forage use efficiency.

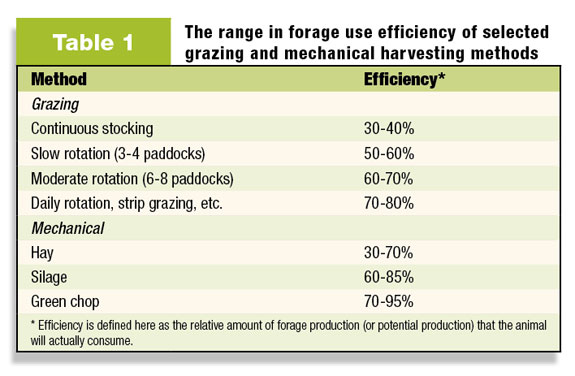

The first step in getting more out of your forage is to exercise more control over the animal’s grazing behavior. If cattle are allowed to freely graze one or two large pastures (i.e., “continuous stocking”), they will select certain areas, avoid other areas and ultimately create a scenario where relatively little of the forage is actually consumed (Table 1).

The key is to ration out the forage. Rotational stocking requires the cattleman to put animals in and take animals out of a pasture in a relatively short amount of time.

Simply splitting large pastures into several smaller pastures (or paddocks) and regularly rotating the animals between them can dramatically increase the efficiency of the forage system.

Producers who allot daily strips for their cattle (strip or frontal grazing) can increase their efficiency even more, often rivaling our most efficient mechanical harvesting methods.

Because of this increase in efficiency, it is possible to increase the land’s stocking rate and carrying capacity.

Stocking rate increases of 35 to 60 percent have been reported. As a general rule, however, stocking rates should only be increased by 10 to 25 percent during the first few years, so as to allow the pastures and forage manager’s skills to improve.

In the meantime, any excess forage production can be harvested as hay or mowed and returned to the soil.

It is important to note that intensively-managed grazing is unlikely to improve the performance (i.e., gain, lactation, etc.) of individual animals.

Forcing the grazing animal to consume forage to a predetermined height eliminates their ability to selectively graze, sometimes reducing individual animal performance (daily gain per head).

This is particularly important when animals with high nutrient requirements like stocker cattle or replacement heifers are rotationally grazed on relatively low-quality forages, such as bermudagrass or bahiagrass.

Though individual animal performance is reduced, remember that it is the increase in stocking rate that results in higher gain per acre.

For producers grazing animals with lower nutrient requirements, like mature cows, this can be a great advantage.

In a three-year study conducted in central Georgia, rotational stocking improved cow-calf stocking rates by about 38 percent and improved calf production per acre by 37 percent without affecting individual cow or calf performance.

The higher stocking rates on rotationally-grazed pastures spread input costs across more animal units (i.e., more cow-calf pairs, steers, heifers, etc.), thereby decreasing cost per cow.

Recycling nutrients in pastures

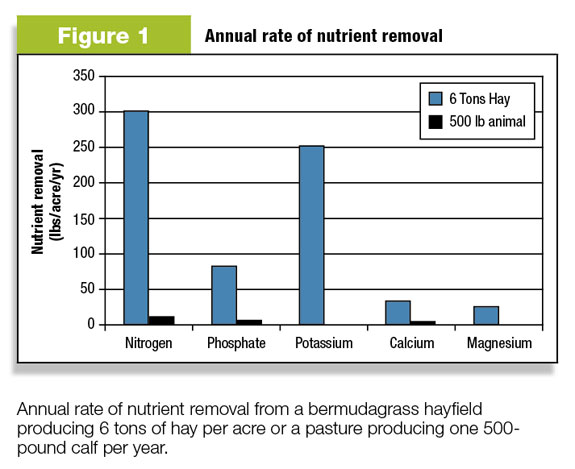

The vast majority of the nutrients consumed by the grazing animal will be deposited back on the pasture (Figure 1).

Of course, without some manipulation of the animal’s grazing habits (and therefore its defecating and urinating habits), the nutrients will not be well distributed.

Poor grazing management can lead to excessive amounts of nutrients around water sources, mineral feeders, shade and gates.

By improving the management of the animal’s grazing, the cattleman can help to ensure those nutrients are more uniformly distributed in the pastures.

In well-managed systems, this may mean that relatively little fertilizer will need to be added. If legumes are also used and the soil is already fertile, there may not be a need to fertilize, except when renovating a pasture.

Using legumes for added N and forage quality

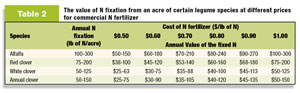

The value of biological N fixation by forage legumes can be quite significant (Table 2). When the legumes represent more than 30 percent of the available forage, this fixed N can provide enough N to meet the needs of the grasses growing with the legumes.

Of course, the prerequisite for this is that the legumes are allowed to thrive.

Management is required

Mixed stands of grasses and legumes generally require more management. This may include annual or periodic planting of legumes into the pasture, maintaining fertile soils and maintaining a canopy height and density that allows the legumes to compete with the grass.

It is in this latter aspect that grazing management is so important. Cattle tend to graze legumes before anything else.

As a result, maintaining legumes in a continuously stocked pasture is nearly impossible. In contrast, maintaining legumes in rotationally stocked pastures can allow adequate recovery between grazings and allow legumes to better compete with the grass.

It is worth noting that one other major benefit of more intensive grazing management is that rotationally stocked pastures usually have fewer problems with weeds.

As a result, these pastures will need fewer (or at least less frequent) herbicide applications, which will allow legumes to be maintained in the stands for longer periods.

Reducing dependency on stored forage

One of the most effective ways to reduce costs in the forage enterprise is to “graze more and hay less.” Strategies like the following can be used to take full advantage of a long grazing season.

• Grazing winter annuals

Winter annual forage crops, such as annual ryegrass and small grain crops, can be used to complement the grazing seasons of our warm-season forage base (bermudagrass and bahiagrass).

Research has shown this practice alone can increase the number of grazing days (and decrease the number of days and the amount of hay feeding) by as much as 80 days.

It is important to realize, however, that these species differ in when these grazing days will be added, because they vary considerably in how quickly they will produce enough forage for grazing and how late into the spring they will continue to provide forage.

• Stockpiling tall fescue

In many areas, tall fescue can be stockpiled (allowed to accumulate) in pastures and hay fields from August through October and grazed later in the fall and early winter.

Tall fescue is an excellent species to stockpile, for several reasons. First, it grows well into fall and thus provides substantial stockpiled forage when conditions are favorable.

Since it often remains green and productive during this time, stockpiled tall fescue maintains high digestibility and palatability.

Despite frost and damp conditions, tall fescue leaves do not deteriorate as quickly as other stockpiled forages. Tall fescue also forms a good sod.

This makes it somewhat tolerant of treading (even during saturated soil conditions). As a result, grazing stockpiled tall fescue during the winter will have a minimal impact on its productivity the following season.

• Stockpiling bermudagrass

Researchers have determined after many years of experiments that stockpiling bermudagrass is a cost-effective strategy to provide winter forage needs.

Economic analyses have consistently shown that stockpiled bermudagrass can be fed for 33 to 60 percent of the cost of making and feeding bermudagrass hay made from the same farm.

The forage quality of stockpiled bermudagrass can also be fairly good.

Research has shown that crude protein (CP) levels are consistently 8 to 12 percent (depending on N fertilization), and total digestible nutrients (TDN) start at 55 to 60 percent at the beginning of the grazing period and end at 51 to 54 percent.

Animals with higher energy requirements can be provided stockpiled bermudagrass, but will require energy and protein supplementation.

Improved grazing management is helpful when extending the grazing season

One intriguing side effect of more intensive grazing management is that it makes it easier to transition between the forage production peaks (March through April for winter annual and cool-season perennial forages and June through August for warm-season perennial forages) and valleys (fall and winter months).

The reason for this is that the rotationally stocked forages are at various stages of development during these transition periods, which allows the grazing of these forages to continue much later than when the available forage is relatively uniform in its growth stage (i.e., forage in one large pasture under continuous grazing). FG

R. Lawton Stewart, Jr.; Ronnie E. Silcox; Curt Lacy; Dennis W. Hancock; Glen H. Harris; and Roger W. Ellis are all from the University of Georgia.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. editor@progressiveforage.com