While these grasses are low input, endophyte-free, drought-tolerant, persistent and produce good gains, they also have a reputation for being finicky and difficult to manage.

Many Fescue Belt grazing publications state that native grasses will not persist under any grazing strategy other than rotational grazing. Clearly, rotational grazing is a good way to manage native warm-season grasses (perhaps the best approach), but is it really necessary?

Many Fescue Belt growers rely on some form of continuous grazing, which is simpler, less management-intensive and requires less infrastructure. Coming from the Great Plains, where native grass rangelands have been continuously grazed since the introduction of barbed wire, it struck me as odd when I was told it didn’t work in the eastern U.S.

My training in rangeland management beat into my head that almost any grazing system is sustainable as long as the stocking rate is appropriate.

The research

In truth, very little information on continuous native grass grazing is available for the eastern U.S. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a three-year (2015 to 2017), production-scale replicated experiment comparing two approaches to continuous, season-long grazing of native grasses. Specifically, we wanted to determine if these approaches were both productive and sustainable in the Fescue Belt.

Our study pastures ranged in size from 18 to 26 acres, which is representative of most Fescue Belt pastures. Pastures were planted in a mix of big bluestem, indiangrass and little bluestem using a 6-3-1 seed ratio, respectively. Pastures were established two to three years prior to beginning the grazing experiment. Grazing was initiated each spring when average grass canopy height reached 12 to 15 inches and terminated when the average height fell below 12 inches.

Nitrogen was not applied during the duration of the study to evaluate “low input” conditions. This lack of any nitrogen amendments would also test the stress level in a “worst case scenario” with plants being on a lower nutrient plane.

To see how the stands were holding up under our continuous grazing strategies, we conducted annual plant and tiller counts each year at grazing initiation. Both plant density and tiller production tend to decrease over time if grazing pressure is consistently too high, resulting in a grass sward with reduced vigor. Therefore, if continuous grazing is sustainable, we expected our annual counts to reflect stable plant population densities and numbers of tillers per plant.

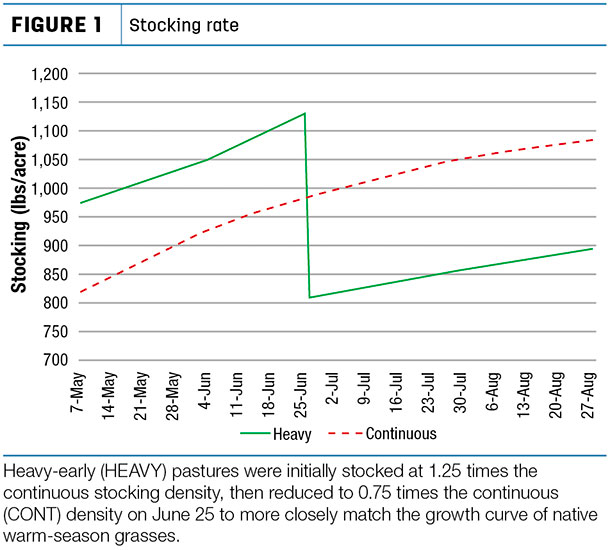

The first grazing strategy was traditional continuous (CONT), season-long stocking. Pastures were stocked with 875 pounds per acre using 600-pound weaned steers. No adjustments in stocking were made during the grazing season. The second grazing strategy, heavy-early (HEAVY), was designed to more closely match grazing pressure to the growth curve of native warm-season grasses.

Native grasses grow rapidly starting in late spring, but after about June 25, they begin to slow down.

Given this growth curve, stocking at an appropriate density is a balancing act; grazing pressure must be heavy enough to keep up with grass growth early in the growing season, but not so heavy that you’re overstocked later in the summer.

We designed HEAVY to circumvent this problem by stocking at 1.25 times the CONT density from grazing initiation through June 25, and then reducing it to 0.75 times the CONT density for the remainder of the summer. In addition to matching grazing pressure to grass growth, other potential benefits of this approach include greater overall gains, increased sustainability of the grass sward and additional flexibility compared to CONT.

By front-loading stocking when the greatest amount and highest-quality forage is available, overall gain per acre may increase. Sustainability may benefit from having fewer mouths on the pasture when grass growth is slow, thereby leaving additional leaf area for plants to build carbohydrate reserves that will help them through winter dormancy.

Finally, while our general rule was to partially destock on June 25, destocking could occur earlier or later, depending on forage availability. (This proved quite useful when a well-meaning graduate student, who shall remain nameless, misjudged forage availability in 2017.)

The results

How did things turn out? In a nutshell, pretty darn good. The average length of the grazing season (both strategies combined) over three seasons was 107 days. Grazing quality forage during this time allows animals to maintain growth without resorting to supplemental feed, allows cool-season pastures to be rested and avoids problems with toxic fescue during the heat of the summer.

There were no statistical differences in animal performance or beef production between CONT and HEAVY. Season-long average daily gains (pounds per day) for CONT and HEAVY were 2.18 and 1.98, respectively. Compared to the minimal gains from grazing hot fescue in the summer, this represents a large improvement.

Furthermore, this rate of gain is appropriate for grass finishing and feeding growing animals, whether steers or replacement heifers.

Farms with fall-calving herds have the additional option of retaining ownership of calves and putting more weight on them before marketing, as opposed to selling at weaning. The number of grazing days per acre averaged 156 for CONT and 152 for HEAVY. Given that average daily gain and grazing days were similar, it’s no surprise that total gain per acre was also similar with CONT and HEAVY, racking up 342 and 303 pounds per acre, respectively.

As discussed earlier, conventional wisdom has been that native warm-season grasses cannot withstand continuous grazing in the Fescue Belt. The results from this project tell a different story. Plant density did not change among the three years. If CONT or HEAVY resulted in excessive grazing pressure, we would expect to see a decrease in plant density.

Another sign of excessive grazing pressure is often reduced tillers numbers per plant. We did see a difference in tiller numbers among years, with 2015 having higher numbers than either 2016 or 2017, which were similar. This could indicate that we pushed the grass too hard in 2015. However, we also used a slightly different sampling method in 2016 and 2017 than in 2015 to decrease subjectivity and increase precision.

The change in method may account for some – or all – of the difference. My gut tells me the change accounts for at least part of the difference, but we have one more round of tiller counts to conduct in May that should help clear things up.

In conclusion, it appears that native grasses are easier to manage than we’ve been giving them credit for. Continuous season-long grazing appears to be a viable management option for farmers interested in grazing native grasses in the Fescue Belt. ![]()

PHOTO 1: Cattle grazing native warm-season grass pastures in east Tennessee.

PHOTO 2: Grass tillers were counted to determine sustainability of continuous grazing of native warm-season grasses in the Fescue Belt. Photos provided by Kyle Brazil.

Patrick Keyser is a professor and director of the Center for Native Grasslands Management at the University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture. Email Patrick Keyser.

-

Kyle Brazil

- Certified Wildlife Biologist

- Center for Native Grasslands Management

- University of Tennessee

- Email Kyle Brazil