Converting pastures from toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue to novel endophyte-infected tall fescue can be a difficult and complex task, given the hardiness of this grass-fungal association and the pervasiveness of toxic endophyte-infected seed.

Several approaches are recommended for killing the existing sward and eliminating any residual seeds. While one approach calls for a specific two-spray schedule – once in late summer and again in early fall – the success of this approach is largely dependent on weather and the timing of the herbicide application.

Another approach for fall establishment involves spraying in the early summer, planting a summer annual smother crop and spraying again prior to planting the new fescue seed. The first spray eliminates most of the actively growing tillers, while the smother crop weakens any missed tillers or newly emerged seedlings before they are wiped out with the final spray.

The time investment required to replace toxic endophyte-infected tall fescue with novel endophyte-infected tall fescue can be intimidating. This may be a factor in the low adoption rates of the novel endophyte technologies. But a recent pasture walk in Southside Virginia revealed one benefit to the intensive spray-smother-spray approach, as well as an important lesson.

The host farmer of this demonstration project began the conversion process by spraying glyphosate on 20 acres in early June. Several varieties of pearl millet and sorghum-sudangrass hybrids were planted a few days after spraying. The fields were also fertilized according to soil test recommendations. Despite the farmer’s best attempts to follow the textbook, the lack of rain for the entire month following planting had him worried that the dry heat, not the crop, would smother any residual fescue.

Unlike nearby cool-season grasses, the warm-season forages rebounded quickly when the first rain arrived over 35 days after planting. Within only 20 days after that first rain, these smother crop varieties yielded on average over 10,000 pounds of dry matter per acre.

Some growing replacement heifers were allocated a small portion of the forage, now at the boot stage, after the nitrate levels subsided following the drought. Most of the field was to be cut for hay, although this large amount of high-quality feed could also be grazed through the summer and early fall, which would allow for the stockpiling of toxic tall fescue in un-renovated pastures. The accumulated fescue forage could then be utilized when alkaloid concentrations have begun to recede in the late winter months.

One lesson learned from this pasture walk was the importance of fertility in achieving not only a high-yielding forage crop, but also in creating the appropriate conditions for smothering, but not inhibiting, tall fescue seedling growth.

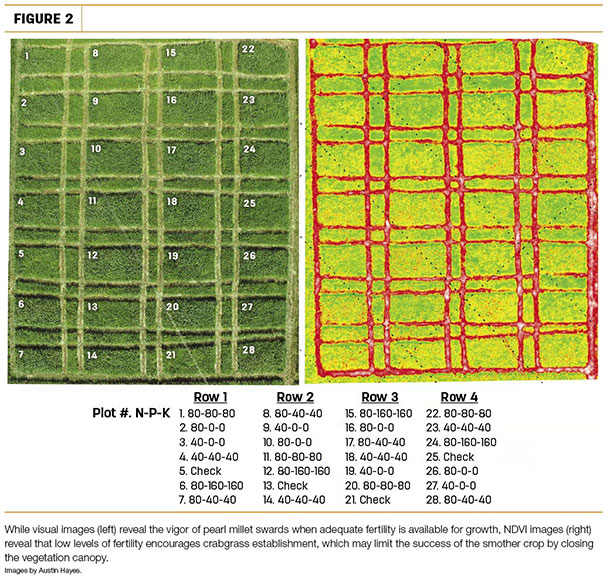

Seven fertility treatments, including a control, were put down with four replications of each prior to seeding the pearl millet. Applying the recommended rate of N-P-K (nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium) according to the soil test (80 pounds of each per acre) resulted in nearly twice the dry matter yield as compared with applying nothing (see Figure 1). The addition of nitrogen resulted in the largest benefits, while the benefits of the phosphorus and potassium applications will likely become more noticeable in the new fescue stand.

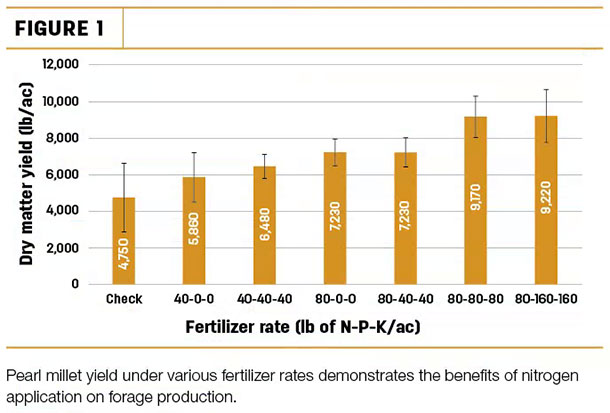

A drone was used to take both visual and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) images (see Figure 2). At first glance, the two images do not seem to correspond; while the high fertility plots appear vigorous in the visual image, the NDVI image indicates more bare ground (red coloration) in those same high fertility plots. Evidently volunteer crabgrass within the low fertility plots skews the photosynthetic activity of the whole plot, making the low fertility plots appear greener in the NDVI images.

Click on the image above to view a larger version.

This is important because the sod-forming nature of crabgrass does not provide the conditions required for remnant tall fescue seeds to sprout and grow. The open swards of grain crops, like pearl millet, are ideal for allowing tall fescue seedlings to emerge but not to flourish. These weak seedlings can then be killed with the final spray before fall planting.

While the conversion process from toxic to novel endophyte-infected tall fescue can seem daunting, the dual-use summer annuals utilized in the spray-smother-spray approach can fill the summer forage gap. It is important to not only sow the correct smother crop species, but also to provide adequate fertility to the plants. This will optimize the growth of the selected, open-canopied crop and minimize the establishment of sod-forming weeds.

If renovation stills seems daunting, the entire process will be covered in more detail at workshops across the fescue belt in 2018. The Alliance for Grassland Renewal, along with university collaborators, will provide detailed instructions on proven techniques for converting to and managing novel endophyte-infected tall fescues.

School dates and locations are:

- March 6: Missouri

- March 8: Kentucky

- March 13: South Carolina

- March 14: North Carolina

- March 15: Virginia

For more details and to register, please visit the Alliance for Grassland Renewal website. ![]()

—From Virginia Forage and Grassland Council

PHOTO: A dense, homogeneous sward of pearl millet allows for high levels of intake at every feeding station selected by this heifer, while also throttling the growth of newly emerged tall fescue seedlings. Photo by Gabriel Pent.

-

Gabriel Pent

- Ruminant Livestock Systems Specialist

- Southern Piedmont Agricultural Research and Extension Center

- Virginia Tech

- Email Gabriel Pent