On some Michigan farms, especially those with single-cut systems, it was an impossible year, even though hay growth was excellent. Saturated clay soils through much of the summer prevented hay harvest altogether in some areas of Michigan’s eastern Upper Peninsula. The result was relatively thick stands of overmature timothy or trefoil hay.

No profitable local market exists for this very low-quality hay. Some fields were never mowed. Other fields were mowed and windrowed then, after repeated rain events ruined the hay, windrows were burned.

Damp windrows failed to burn very well. If left unmanaged, unharvested standing forage resulted in a dense mat on the soil surface over the winter and interference with spring growth and hay harvest the following year.

The question is: “What to do with it?” There are two practical options to consider: burn off the fields or chop the standing hay and return it to the field surface.

Chopping and returning the hay to the field has advantages. Whatever “fertilizer” value is in the hay material is recycled back into the soil as nitrogen (N), phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), potassium oxide (K2O) or sulphur (S).

The disadvantages to chopping are the machinery cost, time invested, potential compaction on wet soils and the possibility of the chopper depositing the material in a heavy swath, which may smother some of the plants underneath. In the short term, this smothering effect may decrease yields but, in the long term, seeds in the swath will germinate and create new plants.

The negatives associated with burning include loss of nutrients, drifting smoke and personal safety hazard. Manitoba Agriculture estimates the nutrient losses from burning small-grain stubble at 90 percent. Estimates of nutrients lost through straw burning from Mosaic Crop Nutrition are more conservative, including 98 to 100 percent loss of nitrogen, 70 to 90 percent loss of sulfur but only 20 to 40 percent loss of phosphorus and potassium.

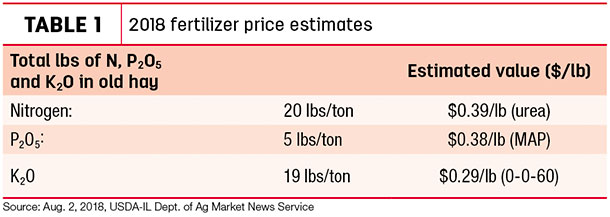

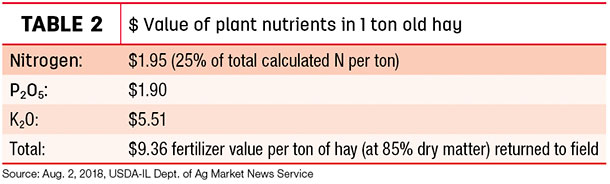

Using feed analysis reports from a Chippewa county, Michigan timothy/trefoil field harvested in early August 2015 (crude protein: 7.37 percent, P: 0.13 percent, K: 0.93 percent), fertilizer value per ton of hay can be estimated (Tables 1 and 2).

N, P and K values are based on 2018 fertilizer price estimates from the Aug. 2, 2018 USDA-IL Dept. of Ag Market News Service.

If the hay is burned and the losses are calculated using the estimate from Mosaic Crop Nutrition, $5.19 fertilizer value per ton of hay burned on the field. MSU Extension estimates the cost of chopping hay at $7.50 to $12 per acre, so we will use $9.50.

The following is a rough estimate of the cost/benefit of chopping versus burning:

Chopping 2 tons per acre hay:

$18.72 per acre estimated fertilizer value of 2 tons per acre hay

- $9.50 per acre chopping

+$9.22 per acre

Burning 2 tons per acre hay (using optimistic ash nutrient values from Mosaic):

$10.38 per acre estimated fertilizer value of ash from 2 tons per acre hay

-$1 per acre burning cost

+$9.38 per acre

Based on this estimate of nutrient return value, there is not a compelling reason to choose one method over the other. However, chopping avoids the potential problems associated with burning.

A third option is to graze the fields. Trampling is more effective than chopping at returning organic matter to the soil because it doesn’t create swaths, and the manure is more available to plants. Obviously this requires access to livestock and a fenced field.

So … what happened in Chippewa County, Michigan? Several thousand acres of unharvested hay were burned in the fall of 2017 and spring of 2018 – roughly 50 to 75 percent of the total hay acreage in the area. Very few, if any, farmers opted to chop and spread. Why? A few key reasons:

- Some farmers didn’t have the equipment needed.

- The clay soil was wet and soft due to the wet season, leading to rutting when equipment was run across fields. Naturally, hay farmers want to avoid this.

- Labor cost and equipment wear considerations encourage burning.

- While burning fields is not a routine local practice, most local farmers have experience and were confident they could accomplish this safely.

When the decision is made to burn a field, planning and safety are essential. Local emergency management officials should be contacted to check on local burning ordinances and regulations.

Fields burned without notice provided to local fire departments can result in very inconvenient, expensive and unnecessary work for the local fire departments. Many Chippewa County farmers made three to five rounds on the outside of their fields and burned these windrows first, creating a “firebreak” when the main part of the field was burned. ![]()

PHOTO: In 2017, farmers in Michigan were faced with rain and wet hay crops, resulting in ruined hay (if they were even able to mow it). Photo by Jim Isleib.

-

Jim Isleib

- Upper Peninsula Crop Production Educator

- Michigan State University Extension

- Email Jim Isleib