This hay-making system’s major limitation is the amount of hay that can be successfully baled and stored before it rains again. I am very familiar with the challenges of making quality hay.

There are limited opportunities to bale dry hay, and if you are making small square bales, you have limited wagons and sometimes even more limited willing workers to unload them.

I encourage farmers to start making hay earlier in May, even if it is in the early heading stage. What little you sacrifice in yield, you will more than make up for in quality and faster re-growth.

If it is going to take you six, seven or eight days of baling to complete your first cutting, you can’t wait until the crop is at its perfect growth stage to cut it, or by the time you cut the last field, it will be way past prime.

Every summer around early June, I have a number of discussions with farmers, busy planting corn and soybeans during the month of May, who haven’t starting making hay yet.

The grass hay is still good-quality, but give it a few more weeks and it will look more like straw in a bale than hay. Rather than drag their first-cutting hay harvest into July, they are considering having someone come in and bale some of it for them.

One option is to work with another farmer who has a big square baler or round baler to come in and bale it for you while the hay still has some good feed quality. In some cases, the other farmer’s cutting, tedding and raking equipment is better sized, so he can do it all.

The next question that comes up is how to fairly split the yield of a first-cutting grass hay crop between the farmer of the hay field and another farmer who has the hay-making equipment and market for the hay.

As you know, this is not a question that has only one correct answer. Some will use the custom rates as a guide for a price base, and others will split the hay. There is no right or wrong answer, but there are some things to consider.

If the custom operator gets a share of the crop, he has a vested interest in getting the hay made in a timely manner. Let’s assume a 2-ton yield of first-cutting dry timothy hay (five large square bales per acre).

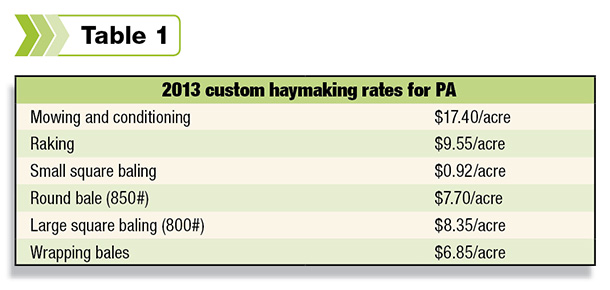

The equipment costs, according to the 2013 Pennsylvania Machinery Custom Rates, to cut, ted, rake and bale large square bales is about $78 per acre or $39 per ton.

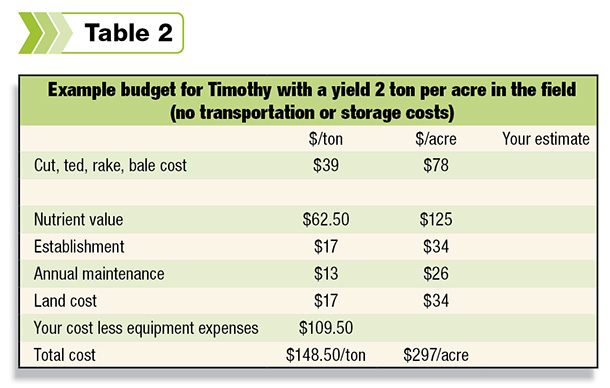

According to the Penn State Agronomy Guide, the typical crop removal of 1 ton of timothy hay is 50 – 15 – 50, valued at about $62.50 per ton or $125 per acre, given a 2-ton yield.

- N=$0.60 x 50 = $30

- P2O5=$0.50 x 15 = $7.50

- K2O=$0.50 x 50 = $25

Also consider the establishment cost of that hayfield, which is at least $200 an acre including lime, fertilizer, seed, soil preparation and planting. Averaging 3 tons per acre per year for four years – that’s 12 tons, which calculates $200 / 12 = $17 per ton.

Annual maintenance is about $40 per acre or $13 per ton = Fertilizer spreading, spraying herbicide and miticide.

Land cost or rental value = $25, $50 or $100 (take your pick – I’ll say $50 per acre per year, which is $17 per ton).

If we add up all the costs not associated with cutting and baling, you have about $110 per ton invested before you start cutting.

Add the equipment cost of $39 per ton to the $110; you’re up to about $150 a ton and you haven’t even hauled it or stored it yet.

So how do you come to a fair agreement if you are going to share the hay with the person who made it for you? Since about two-thirds of the cost of the hay is upfront, and one-third of the cost is from making the hay, I would start the discussion at one-third of the price to the custom operator and two-thirds for the farmer who is managing the fields.

If the fields are not being managed aggressively, and yield is less than 2 tons per acre, I would consider closer to a 50-50 split of the hay crop.

A similar model can work for wrapped baleage or straw. They key is having a market for the hay, baleage or straw before you enter into an agreement. Simply baling it and stacking it on the edge of the field to deal with later is not a viable option.

Looking at the Pennsylvania regional hay auction reports in the paper in mid-December 2013, I see common prices for grass and timothy hay are from $150 to $200 per ton with a high of $330.

Most of these prices are for big square bales, not small bales. Depending on your market, small bales will sell for approximately 30 percent over big bales because the end user doesn’t need a machine to handle them.

It suggests to me that maybe all this work, hidden expense and risk to bale dry hay isn’t as profitable as one might think.

As you know when marketing your hay, customer service and knowing what your customer wants are critical. If they want small bales, there are many machines on the market now such as accumulators, stacker wagons, grapples, bundlers and re-baling equipment to increase your efficiency while reducing the labor associated with small square bales.

Of course, they all come at a price, and depending on your scale, they may or may not be a good business decision for your farm. FG

PHOTO

Baling with a large square baler in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, at a Penn State Extension bale-handling field day. Photo by Andrew Frankenfield.

Andrew Frankenfield

Agronomy Educator

Penn State Extension