In addition, different types of roads (federal, state, county, township, etc.) may also have specific regulations about the time of year forages must be cut or removed from the ditches. These and other factors may influence hay quality; currently, little is known about the nutrient content of ditch hay, the amount of ditch hay harvested or the intended use of ditch hay in many areas.

This summer, the North Dakota State University Extension Service initiated an effort to answer some of the key questions surrounding ditch hay quality and usage. County extension agents were critical to the success of this effort, with agents from 29 counties enthusiastically volunteering to aid in collecting and characterizing a limited number of samples.

To standardize data collection, training was conducted for all participating staff. Specific information gathered during the evaluation included the county where hay was produced, cutting date, whether hay was rained on, type of binding material used, type of plant species present in hay and type of road adjacent to ditches.

Additional information was also collected regarding the miles of ditch hay baled by producers, percentage of hay inventory represented by ditch hay, target species for feeding hay and whether hay was going to be fed on the ground, in a hay feeder or as part of a total mixed ration (TMR).

County agents collected a total of 182 samples from 36 different counties. Samples were limited to a single sample per producer. Each sample was analyzed for concentrations of dry matter, crude protein neutral detergent fiber, acid detergent fiber, in vitro organic matter digestibility, calcium, phosphorus and calculated total digestible nutrients.

As expected, great variability was observed in amount of ditch hay harvested and relative reliance on ditch hay as a staple feedstuff among operations. Producers harvested anywhere from a half-mile up to 100 miles of ditch hay, with the average being 9.7 miles. Similarly, the proportion of hay inventory represented by ditch hay ranged from 0.2 percent to 100 percent, with 21 percent being the average.

We did not collect information regarding the number of animals maintained by each producer sampled, so we don’t know if larger operators had less reliance on ditch hay as a feedstuff.

Plastic twine (40.6 percent) and net wrap (40 percent) were the bale binding materials most often used, with a smaller proportion of bales being bound with sisal twine (19.4 percent). A majority of the hay sampled was going to be fed to cattle (about 90 percent), with the remaining proportion split among horses, sheep and bison. The feeding method indicated most often was using a bale feeder (63.9 percent), followed by feeding on the ground (36.8 percent) and feeding with a TMR (11.6 percent).

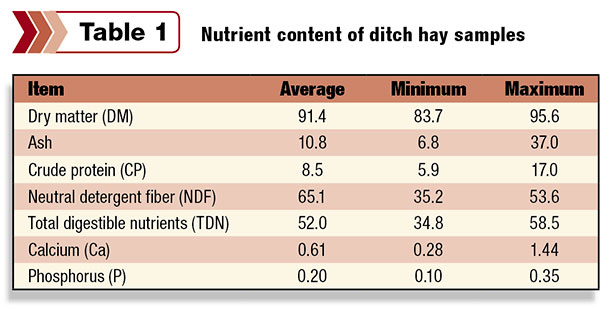

Variability was also observed in the analyzed nutrient content of the forages (Table 1). Some samples tested were extremely high quality, whereas quality of other samples was poor.

Unpaved roads in several parts of North Dakota experience heavy traffic related to oil-field activities, and dust has the opportunity to collect on standing and cut forages from ditches adjacent to these heavily used roads.

Dust contamination was noted in several of the samples taken for the core oil-field counties, with ash content (essentially inert, indigestible material) reaching a maximal value of 37 percent, compared with our average value of 10.8 percent.

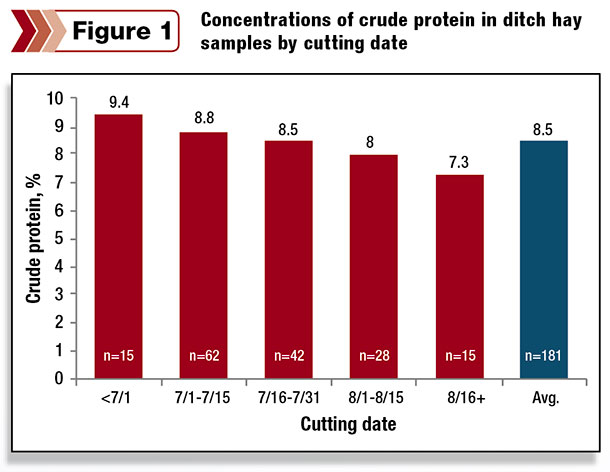

Cutting date of samples ranged from June 10 to Sept. 10. Concentration of crude protein in samples was impacted by cutting date, with forage harvested early in the year having greater concentrations of crude protein compared with those harvested later in the year (Figure 1).

This trend was expected as protein content of standing forages decreases with plant maturity over the course of the growing season.

Across North Dakota, road ditches are comprised of cool-season introduced grass species, the most common being smooth bromegrass. These species initiate growth early in the spring and reach peak production in early July.

To achieve the best combination of quality and quantity, this would be the optimal time to harvest; however, specific regulations regarding the timing of ditch hay harvest for roads under certain jurisdictions may prohibit harvesting forage of optimum quality.

Approximately a quarter of the samples submitted were rained on during the interval from cutting to baling. The number of days the forages were wet in the swath ranges from a half-day to more than 14 days, with four days being the average.

Rain was associated with an increased ash content, and the TDN content of samples that had been rained on was 2 points less than those that had not been rained on.

To understand the variation in forage quality across the state, samples were divided to represent eastern and western regions. Region did not impact protein content of the forages, but acid detergent fiber and TDN were both impacted.

Samples from the eastern region had greater TDN (via reduced acid detergent fiber) compared with samples from the western region. Variations in soil type, temperature and moisture between regions all likely contributed to the differences observed.

Results of the project allowed us to understand the variation in quality of ditch hay within a single year’s harvest and factors contributing to that variation. Results reinforce the importance of testing nutrient contents of individual feeds to ensure appropriate delivery of nutrients to different classes of livestock.

Individual reports of the nutrient content of sampled hay are being distributed to participating producers along with appropriate feeding recommendations. FG

Miranda Meehan is an NDSU Extension livestock environmental stewardship specialist.

PHOTO: Baling ditch hay is a common practice in North Dakota, and a recent study by university extension specialists helped define nutrient value. Photo provided by Carl Dahlen.

Carl Dahlen is an beef cattle specialist with North Dakota State University. Email Carl Dahlen.