Some of those decisions for alfalfa include harvest timing in the fall and providing adequate potassium, both crucial to having strong plants that can survive severe winter and come back the following year with good yields. Buildup of energy reserves stored in the roots is part of the outcome of those decisions and is key to how plants withstand severe winter conditions.

If energy reserves are low, the hardening of alfalfa is weak and injury from low temperature, smothering under ice sheets and heaving later in the spring, will be more likely.

As indicated by producers and crop consultants in survey reports that investigated the alfalfa winter injury in Minnesota and Wisconsin from the winter of 2012-2013, the conditions associated with the alfalfa stand killing aftermath were the combination of low soil moisture during late summer, dry fall, freezing rain and lack of snow cover.

Recent changes in weather patterns in Minnesota and Wisconsin have been characterized by increases in winter temperatures, with late snow and ice in the fall and an early start the following spring – masking in this manner, disastrous weather responsible for winter injuries.

In the upper Midwest, we expect cold weather and plenty of the insulating snow cover in the winter, but these recent occurrences remind us of the old adage “… the weather that we get may deviate from the climate that we expect.” It is important to review the buildup of plant reserves and associated management factors for informed fall management decisions.

Building up reserves

The importance of carbohydrate reserves in regrowth of alfalfa has long been recognized. Cool-season perennial legumes like alfalfa and other clovers use the sugars coming from photosynthesis and store them as reserves for later use. The storage material is called carbohydrate reserves, energy reserves or nonstructural carbohydrates.

Storage energy in plants is built into large chains made up of simple sugars that can be quickly converted back to the simple forms for quick availability when the normal energy levels of the plant are low or for emergency responses. Starch is the storage energy in alfalfa and other cool-season legumes, and fructans are the reserve sugar in cool-season grasses.

In forage plants, this energy reservoir is produced during the day and stored as granules ready to be used when the plants need them.

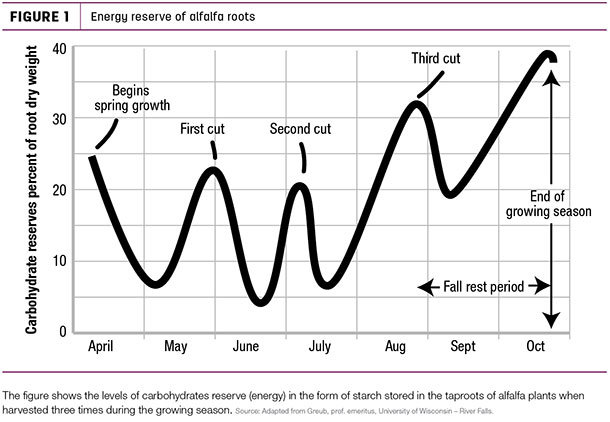

In the case of alfalfa, the starch is stored in the roots, more specifically in the taproot, from where it is “drawn” and used in plant functions. The reserves undergo cyclic utilization and restoration periods throughout the harvest season, but the balance of reserves needs to be positive before utilization, and high (close to 40 percent) going into fall (Figure 1).

If we used the graph as a visual instruction, right before spring growth begins, under normal conditions, the plant reserves at this stage (measured as root reserve or percent of the dry root weight) are about 25 percent.

As the season progresses, or after defoliation (by cutting or grazing) the reserves are mobilized for plant growth and maintenance. Cutting at first flower (10 percent bloom) allows for root reserves to be restored. This stage is also the best compromise between yield and quality.

Toward the end of the season, high carbohydrate reserves are necessary for best winter survival. These reserve levels in the root need to be around 30 to 35 percent and can be achieved with a fall rest period. A fall critical period occurs from mid-September through mid-October. In the case of northern Wisconsin, River Falls area, this would be around September 7.

It will begin earlier if further north or later if further south. The level of risk is increased as fall cutting is done later. With improved genetics, better winter survival (faster shoot regrowth) and disease resistance, risk can be minimized.

Also important in the process of storage buildup (or starch synthesis) is the presence of potassium. This is an important nutrient, not only involved in the transport of new products from photosynthesis and conversion to storage form, but also in the process of storage food mobilization.

The buildup of reserves or conversion of simple sugars to complex storage sugar (starch) in alfalfa and forage plants is disrupted by deficiencies in potassium. Research results show high soil potassium fertility reduces the stress produced by fall cutting practices and is essential for long-term persistence of alfalfa.

In summary, the harvesting management of alfalfa is critical for achieving the yield and quality desired out of the harvested material. Fall decisions will be determinant in persistence and longevity of the stand. Weather-damaging conditions can be somewhat anticipated through advances in weather forecasting and apps, but we really do not have any control on the weather.

We can, however, minimize risk by allowing enough time for alfalfa to restore adequate carbohydrate reserve levels. If plants are harvested repeatedly or too late in the fall, there may not be sufficient time for reserve buildup going into the winter and stand persistence will be compromised. ![]()

PHOTO: The figure shows the levels of carbohydrates reserve (energy) in the form of starch stored in the taproots of alfalfa plants when harvested three times during the growing season. Source: Adapted from Greub, prof. emeritus, University of Wisconsin – River Falls. Photo by Yoana Newman.

Yoana Newman is a forage specialist with University of Wisconsin – River Falls. Email Yoana Newman.