The Progressive Forage legume ID contest, published in the September 2020 issue of Progressive Forage, was won by Terry Friskel of Kirkland, Missouri.

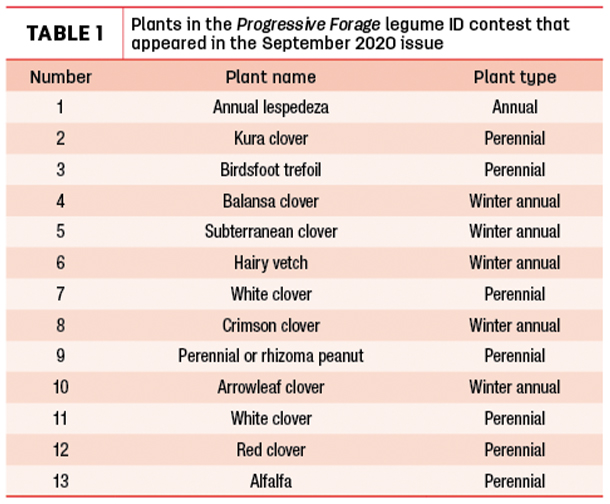

Working with the 13 photos submitted to Progressive Forage by Keith Johnson of the Purdue University Crop Diagnostic Training and Research Center; Jimmy Henning, University of Kentucky Forage extension specialist; and Dennis Hancock, center director – U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center, Friskel correctly identified all but one of the legumes shown in Table 1.

“I was raised as a city boy in the St. Louis suburbs,” said Terry Friskel. “My appreciation for plants began developing at an early age. Due to my kindergarten teacher, Mother Columba, instilling in me the value of reading, I continue as an avid reader. In addition to other subjects, I read everything I can find on forages and their relationships in the environment.

My plant education is continually strengthened by attending forage conferences, seminars, workshops and field days, where I learn from the experts. I don’t normally enter contests, but the Progressive Forage legume ID contest caught my attention, and I couldn’t resist testing my skills.”

Due to his love for plants, Friskel obtained a bachelor’s degree in biology from Rockhurst College in Kansas City. Using the degree as a science platform, he pursued his second passion in dentistry from the University of Missouri – Kansas City. After graduation, Friskel established a dental practice in DeSoto, Missouri, from which he retired two years ago after practicing for 39 years.

“Until a year ago when my wife, Donna, passed away, she attended meetings throughout the Midwest with me. After she was unable to walk, I pushed her around the conference halls in a wheelchair. She never lost interest in our shared appreciation of plants and was an avid gardener,” said Friskel. “To further expand our interest in plants, we purchased a farm near St. James, Missouri, in Phelps County. Being a good Catholic woman, she immediately named the farm Isadore Farms. St. Isadore is the patron saint of farmers.”

Isadore Farms is in an excellent area for growing forage to provide grazing and hay for Friskel’s Angus cattle. The farm is in the Big Prairie area of the county below the foothills of the Ozark Mountains. In its natural state, Big Prairie supports tall native grasses such as indiangrass, switchgrass, little bluestem and big bluestem. According to the USDA-NRCS soil survey, farming is the main enterprise in Phelps County, with forage accounting for the largest percentage of crops. Cool-season grasses and shallow-rooted legumes are the primary forage crops. A small amount of acreage in the county is devoted to row crops and small grains. Several wineries are also located in the St. James area.

Phelps County weather is ideal for growing forage to supply the numerous dairies and beef cattle operations. The county soil survey describes the winter climate as an average temperature of 33ºF and an average daily minimum temperature of 23ºF. In summer, the average temperature is 76ºF, and the average daily maximum temperature is 87ºF. Total annual precipitation is approximately 42 inches, with 66% of that occurring in the April-through-September growing season. Average seasonal snowfall is about 17 inches. Midafternoon relative humidity averages about 60%, rising to about 83% at dawn. The sun usually shines 66% of the time during summer and 48% of the day in winter.

“Legumes grown on Isadore Farms include clovers (ladino, red and white) and a small amount of alfalfa. Planted pastures and hay fields contain orchardgrass, brome, timothy and fescue,” said Friskel. “I purchased some adjacent native prairie pastures consisting primarily of indiangrass and big bluestem.”

Sustainable management is exercised on the entire Friskel farm. Soil is covered with vegetative cover year-round to protect it from erosion, hard pan development and soil microorganism population decreases. Lime and trace minerals are applied biannually in accordance with soil analysis recommendations.

Plant diversity is maintained, which helps promote soil microorganism diversity, resulting in improved soil health. Stocking rates are regulated so enough foliage remains to facilitate plant regrowth. Rotation grazing is practiced to allow pasture recovery from grazing and, in the near future, Friskel plans to install more cross fencing to allow for longer pasture rest periods.

“Minimally used roads are utilized as longitudinal food plots to provide wildlife nutrition and to slow their travel across the farm,” said Friskel. “We have deer, turkey and numerous bluebird nesting boxes throughout the farm. The plots are maintained year-round with plant species such as turnips, radishes, cereal rye, triticale, wheat and various legumes. I continually evaluate plants that might contribute to deer, cattle and soil welfare. My friends are allowed to hunt on the property, and I enjoy watching and photographing wildlife.”

Friskel firmly believes that legumes play an important part in pasture management. He plants legumes in grasses to aid in cattle bloat prevention, to improve animal body condition and serve as a wildlife attractant. With adequate potassium applications, white clover provides forage continually through spring and summer. Friskel firmly believes vegetation management is a basic skill required for successful livestock production and wildlife conservation.