Let me make clear from the outset that frost seeding will never be as effective as methods that place seed below the soil surface. The best method for new seedling establishment is seeding at the proper depth into a tilled seedbed or no-till drilling into a killed stand.

The next most successful method is no-till drilling into existing stands, and the third most effective is broadcasting into existing stands. Frost seeding fits into the last category.

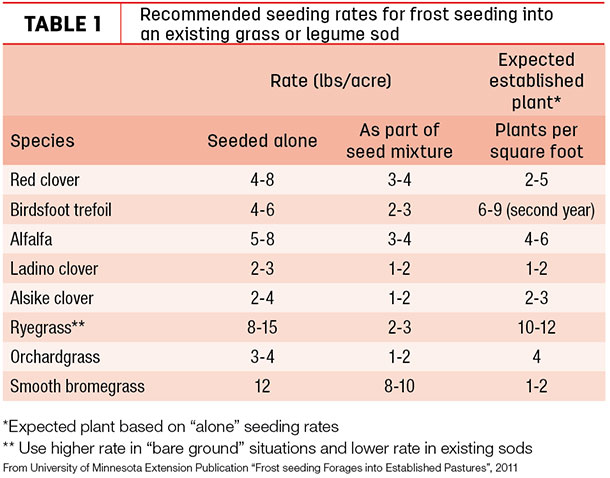

Table 1 has a good overview of seeding rates and expected established plant populations when frost seeding. The best time to seed is while the ground is still frozen but thawing on top during the day – usually February to April depending on location.

You might ask, why even bother with frost seeding if it is the least effective method? Frost seeding is easy to do and by far the lowest cost per acre of any of the seeding methods. If you ran out of time last fall and will be busy with typical spring seedings, frost seeding can be done earlier in the year so you don’t have to try to fit it in during typical planting time.

As the name implies, frost seeding uses the freezing action of soil to its advantage. In late spring, when the days are above freezing, the surface of the soil thaws. If the temperatures at night are below freezing, the soil will freeze again at night.

Each time this happens, the soil cracks and heaves a little bit. There can be numerous repetitions of this cycle during spring, and the more repetitions there are, the better for frost seeding.

What seed to use

Given that explanation, there are a few things that drive what kinds of seed will work in this scenario. First, seeds that can germinate at lower temperatures are a must. The best-case scenario is that you frost seed while the ground is still frozen and at first thaw.

The seeds sprout and establish often before you could ever think about doing ground prep in the spring.

The second requirement is a small seed size. For frost seeding to work, the seed needs to fall into the cracks of the frozen soil surface and then be covered by the next thaw. Large seeds like peas will probably never get below soil surface this way. Small seeds like clover are better suited.

When frost seeding, we need to use species that can germinate in cold temperatures and are small enough to be worked into the soil during repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

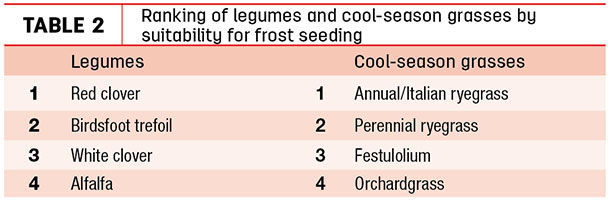

Table 2 lists legumes and cool-season grasses ranked by suitability for frost seeding. While this list could be different depending on who you ask, the number one legume and number one grass are clear winners in each category.

Red clover is easily the most prevalent legume used in frost seeding for one simple reason – it works. Red clover seed is small enough to get worked into the soil and the seedlings are very aggressive – both good things for frost seedings.

Of the grasses, the annual or Italian ryegrasses are clear winners, while the others have decent success. Annual ryegrass has been documented to germinate (albeit slowly) in soil temperatures of 40 degrees.

And once germinated, no grass has better seedling vigor than annual ryegrass. If you are up on your grass species, you will notice the first three are all somewhat related, then along comes orchardgrass.

In my opinion, the only reason orchardgrass makes this list is that it has really good shade tolerance that allows it to compete with the established stand. For me personally, I don’t even try frost seeding with anything but annual ryegrass.

Management considerations

A third thing to consider is the condition of the stand into which you are frost seeding. If you had a dense sod and left 3 or more inches of residual going into winter, the success of frost seeding will be limited. Many of the seeds will come to rest on the residue you left and never reach the soil. The ones that do reach the soil will have difficulty competing with the vigorous plants that will grow rapidly once spring arrives.

So perhaps the ideal stand for frost seeding is one that you really thought about addressing last year, but just didn’t quite get there. If you couldn’t see at least some thin spots and small patches of bare soil, your success will be limited.

Another place to think about using frost seeding is in stands that were grazed to the ground before or during winter. If you winter cows on the same fields all winter and don’t move them off until after spring greenup, frost seeding can really help keep those stands productive for future years (and some hoof action will help with seed/soil contact).

If you study Table 2 again, you will notice that the best choices for frost seeding are not long-lived perennials. On the legume side, red clover will last two and perhaps three years, while on the grasses, annual or Italian ryegrass will be a one-, perhaps two-year plant. It seems we can’t have it all in nature and often the plants that establish vigorously don’t last long.

From a management point of view, this means that frost seeding may need to be done every year or two if that is your primary method of planting these species.

This is more common than you may think. In transition zone states like Kentucky, many producers rely on red clover as a staple legume, and the only way many of them plant it is by frost seeding. Frost seeding can be very effective as a long-term management practice.

To put frost seeding in perspective, I’ll end with this: If you absolutely are in need of feed, don’t bet the farm on frost seeding. It won’t work every time. But with regular usage over time, frost seeding can become a valuable tool that results in beautiful stands while reducing rates of absolute stand failures across your whole operation. ![]()

-

Chad Hale

- Research and Acquisitions Manager

- Western Forage Resources

- Email Chad Hale