The type of fertilizer must be considered because fertilizers differ in their cost, effectiveness and efficiency, as is the case when comparing granular and liquid fertilizer forms. Fertilizing at the rate where maximum economic yield is obtained is difficult to achieve in practice since the response of the forage to the fertilizer may not be known, and the forage price may also not be known. If crop growth increases at all with application of fertilizer, this is usually an indication fertilizer application is economical at current fertilizer costs and forage prices. Soil and plant tissue testing, and other fertilizer management tools, can be used to increase the chance the fertilizer rate is close to the economic optimum.

Diminishing returns

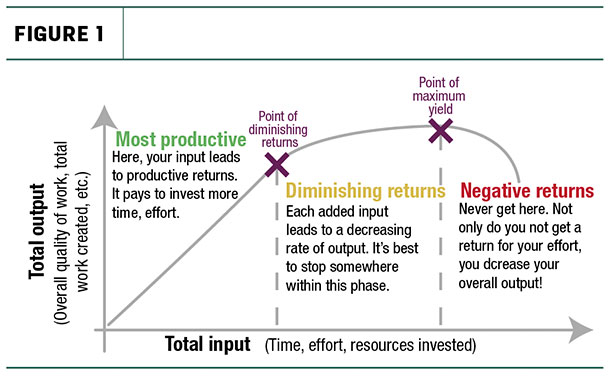

Diminishing returns refer to a decreasing rate of output with an increasing rate of input. This basic concept when applied to crop production tells us at some fertilizer rate the increase in yield from applying an additional unit of fertilizer slows, and this is called the point of diminishing returns. A point may actually be reached at increasingly higher fertilizer rates where additional fertilizer application may actually decrease yield due to lodging or other factors, and this is called the point of negative returns (Figure 1).

The maximum economic return will always be at a fertilizer rate less than the maximum yield. The reason is the cost of the fertilizer must be paid for by the increase in yield. The fertilizer rate where maximum economic yield occurs is often arbitrarily set at 95% of biological yield for conceptual purposes, but this value can vary depending on fertilizer cost, crop price and harvest cost.

Granular versus liquid fertilizer

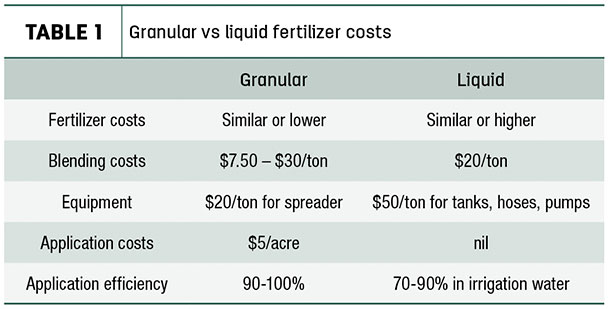

The costs of granular versus liquid fertilizers can vary depending on the fertilizer, region and forces in the marketplace (Table 1). Liquid fertilizers are often thought of as more convenient than granular forms, particularly in irrigated agriculture. Fertilizers in liquid form lend themselves to being dripped into irrigation canals or injected into pressurized irrigation systems. The application costs of applying liquid fertilizer forms into irrigation water is often minimal unless application equipment is rented.

Granular fertilizer is usually applied with ground-based applicators with an application cost of $5 per acre or more. The convenience in using liquid forms must be balanced with cost and effectiveness of the fertilizer. Both granular and liquid forms of fertilizer can be subject to volatilization losses reducing fertilizer use efficiency, but water-run fertilizer has the unique disadvantage of only being as efficient as the irrigation water distribution uniformity.

Fertilizing to a point less than maximum yield

Due to diminishing returns, the maximum economic yield (MEY) is less than maximum biological yield, because maximum yield does not consider the cost of fertilizer or harvest and hauling costs. Putting this theory in practice is difficult because the fertilizer rate which produces maximum yield is not known precisely, and often the commodity price may not be known either. The economic risk of applying less fertilizer than needed by the crop is usually greater than applying too much fertilizer. Also, forage crops often do not have reduced yields at excessive nitrogen rates, as is common with many grain crops, but rather, the yields may just plateau.

Determining the economically optimum fertilizer rate

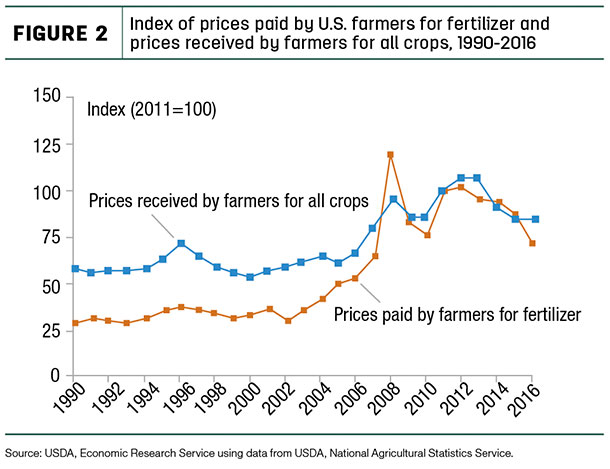

The economically optimum fertilizer rate is usually difficult to determine due to lack of information. The increase in yield with each increment in fertilizer is usually not known. However, we do know the economically optimum fertilizer rate is less when the fertilizer cost is high and/or the forage price is low (Figure 2).

Using an example from Arizona, alfalfa yield has been increased by phosphorus fertilizer application by up to 10%. Assume the following:

1. Annual yield without fertilizer is 10 tons per acre

2. Applying 200 pounds per acre of mono-ammonium phosphate (MAP, 11-52-0) will increase yield by 10% or 1 ton per acre

3. The price of MAP is $500 per ton, so 200 pounds per acre of this fertilizer costs $50 per acre.

Then, $200 per acre worth of alfalfa yield was achieved with $50 per acre in fertilizer cost. If we assume harvest cost is $50 per ton, then this number should be subtracted from the $200 per acre gain, so the harvest cost adjusted gain is $150 per acre in forage yield from $50 per acre in fertilizer. So, the breakeven for fertilizer application would be a tripling of fertilizer cost ($1,500 per ton MAP) or a reduction in forage price to one-third of the value used in this example ($67 per ton forage).

This example shows that based on current fertilizer and commodity prices, fertilizer application is beneficial with even a small crop response, but the economically optimum rate may not be known. Using soil and plant tissue testing or other fertilizer management tools is often the best way to be assured that your fertilizer rate is close to economically optimum. ![]()

IMAGE, FIGURES AND TABLE: Provided by Mike Ottman.

Mike Ottman is an extension agronomist at the University of Arizona. Email Mike Ottman.