But harvesting it has always been a balancing act between quality and yield due to the differences in leaves and stems. Current harvest practices to minimize total fiber (before the stem gets too mature) require cutting the alfalfa frequently (every four to five weeks).

This creates an economic disadvantage to produce a high-quality forage because of the physical and mechanical inputs and the challenge of having enough good weather for these frequent harvests.

There is a need for a harvest management system that requires fewer harvests and extends the harvest window for each harvest but produces the desired amount and quality of forage.

At the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center (USDFRC) USDA Agricultural Research Service in Madison, Wisconsin, along with colleagues at the University of Wisconsin, we’re in the early stages of developing a system that harvests alfalfa leaves separately from stems and creates two component streams: One that is protein-rich (leaves) and one that is fiber-rich (stems).

Such a system would benefit the management, agronomic and herd performance facets of the farm. Previous research at the USDFRC estimated that this strategy could reduce the risk of adverse weather on crop harvest and increase yield by capturing 30 percent of plant material typically lost with current harvest practices.

And this alternative reduces the frequency at which the crop needs to be harvested by at least 25 percent, a potential major savings in labor and fuel.

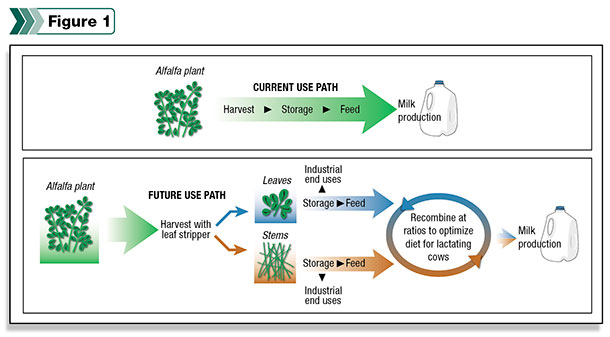

As shown in Figure 1, this system also provides the producer with the opportunity to recombine these in proper proportions to create the desired quality of diet for many classes of cattle. It also creates possibilities for using the components for industrial or other end uses.

As shown in Figure 1, this system also provides the producer with the opportunity to recombine these in proper proportions to create the desired quality of diet for many classes of cattle. It also creates possibilities for using the components for industrial or other end uses.

Building a novel concept such as this from start to finish requires years of research; you won’t find this type of forage harvester at your local implement dealership anytime soon.

But it’s important to know research is looking for ways to get more feed value out of crops and to encourage the planting of soil-conserving perennial forages such as alfalfa.

The first several prototypes of the machine, colloquially called a “leaf stripper,” were developed by Kevin Shinners, an agricultural engineer in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, with support from the USDFRC and the College of Ag and Life Sciences at the University of Wisconsin.

His former graduate student, Matthew Digman, built the recent prototype while a researcher at the USDFRC. Digman, along with colleagues at the University of Wisconsin, also researched methods for making and fermenting alfalfa juice from the leaves for potential use as a protein source in food or industrial products.

These prototype machines work by stripping the leaves from the stems, collecting the leaf portion and leaving the stems behind to be cut and windrowed at a later date.

These prototype machines work by stripping the leaves from the stems, collecting the leaf portion and leaving the stems behind to be cut and windrowed at a later date.

Since the leaves are ensiled directly after harvest and not allowed to wilt, early studies utilized “mini silos” (aka glass jars) to determine if this high-moisture leaf fraction could be ensiled. When that proved successful, small silage bags were tried next; while there was a lot of effluent, the leaves did ensile successfully.

First farm-scale trial

In 2013, we scaled up the research. We wanted to determine if leaves and stems harvested separately from mature alfalfa could be recombined in appropriate ratios to perform as well as whole-plant alfalfa haylage in dairy cow diets. For the control diet, alfalfa was harvested with conventional methods in the typical early bud stage (fourth cutting, Aug. 25, 2013) and ensiled in regular silage bags.

Silage inoculant was applied at the time of ensiling. On Sept. 12, 2013, when the alfalfa was at the late full-bloom stage, leaves were harvested separately from the stems with the prototype leaf stripper; the leaf fraction still contained 35 percent stems. The leaf and stem fractions were ensiled separately in regular silage bags.

Although the leaf fraction was only 22 to 24 percent dry matter at the time of ensiling, it ensiled quite nicely and produced a high-quality silage. We are currently analyzing samples of this silage to determine the quality and extent of fermentation and whether or not it varies greatly from normal haylage.

For the feeding trial, 44 first-lactation cows were randomly assigned to one of two diets. The experimental diets were formulated to provide similar concentrations of crude protein and neutral detergent fiber by blending two whole-plant alfalfa silages or by blending separately ensiled alfalfa leaves and stems.

The feeding trial lasted 24 days. Cows were milked three times a day and averaged 90 pounds of milk per day.

There were no significant differences between the two cow groups. Cows had similar levels of intake between the two diets, and there was no bodyweight change for cows during the experiment.

Milk production and milk composition did not differ between the two diets. Nitrogen use efficiency (as measured with MUN) did not differ between diets. A longer-term feeding study is needed in order to evaluate the impact of the diets on bodyweight gain or loss and to assess any collateral effects on lactation performance.

Based on these preliminary research results, we believe this system has promise and we will continue to pursue various possibilities.

We will soon be building the next generation of leaf stripper equipment in an attempt to improve its efficiency at separating leaves and stems. Anyone with comments or suggestions from a forage grower’s point of view is welcome to email me. (Please put “leaf stripper” in the subject line.) FG

PHOTOS

PHOTO 1: Prototype leaf stripper harvesting alfalfa leaves. The remaining stems were cut and then harvested with a conventional forage harvester.

PHOTO 2: Alfalfa stems remaining in the field after leaves were removed. The leaf fraction was 65 to 70 percent leaf material. Stem fraction was 16 to 17 percent leaves. Photos courtesy of Ronald Hatfield.

- Ronald Hatfield

- Research Plant Physiologist - U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center

- USDA Agricultural Research Service