The main question to ask about your operation is: Are you converting as much sunlight as possible every day of the growing season? Any day the temperature is above freezing, you could theoretically be growing forage. So as we evaluate our operations, it is important to understand when our forages grow and when they don’t.

Finding the holes

If your forage system includes annual plants, it is easy to find the holes in your forage system. When growing corn silage, the fields can be bare until late spring when the corn is planted and is bare again in the fall after corn silage harvest. The early spring and late fall time frames are windows of opportunity for growing forage.

The temperatures might not be high enough at that time to grow corn, but they will grow cool-season plants. Growers in colder regions with some grain hay in the system often leave the ground bare from late summer’s harvest until spring planting.

This late summer time frame would provide a window of opportunity to grow more forage rather than waiting until spring to plant the next crop. Taking advantage of these brief windows can pay huge dividends in forage yield and quality.

Perennially based systems do a pretty good job of capturing sunlight. The plants are there for years at a time, exposed to the sun all through the growing season. Identifying holes in these systems isn’t as cut and dry as seeing a bare field with nothing growing. The question for perennial systems is: Could I be growing forages at a faster rate than my perennials are growing?

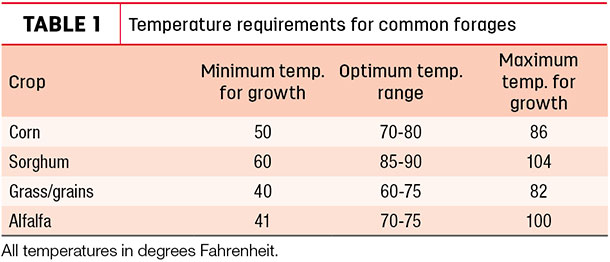

To address this question, it is helpful to think of the temperatures that are best suited for each type of plant we can grow. Just from simple observation, we know that systems based on cool-season grasses slow down in the hot summer. Alfalfa does too, just not as much as grass. In Southern bermudagrass-based systems, there isn’t much growth in the spring or fall.

These times of slow growth in either cool- or warm-season forage stands are the holes in perennial systems. Table 1 lists some of the important temperature requirements for some common forages.

Are you asking a forage to perform outside its comfort zone? If so, you are creating a small hole in your forage program.

Filling the holes

There are several options we can use for filling these gaps. The readership of this publication stretches from the Gulf of Mexico into Canada. There is no “one-size-fits-all” solution. The purpose of this article is to help us all think critically about our forage system and what we can do to maximize it. Some examples might be helpful.

On operations with corn silage, double cropping with a winter grain is one of the best ways to maximize growth per acre. Planting a winter grain like triticale after corn silage harvest allows the plants to establish in the fall and take off as soon as temperatures get above freezing in the spring.

You can produce several tons of dry matter before you could ever get out on your fields for a spring planting. Admittedly, it is easier to double crop the farther south you are, but there are farmers in the northern U.S. and even in Canada that are successfully using this approach.

One thing you may have to consider is using a shorter-day corn to allow more time for growing the small grain. This is a hard pill to swallow for many growers, but research has shown that over the long term, switching to a corn hybrid that is 10 days earlier may cause you to lose 3 tons of silage (1 ton of dry matter). This trade-off can be well worth it if that sacrifice results in 2 to 4 dry matter tons of small-grain forage.

For those who plant small grains for a summer forage harvest, late summer is often the best time to establish cool-season grasses and alfalfa. An added bonus to this approach is that summer-planted stands are fully established by the following spring and give full production in their first harvest year.

This is one way to escape the struggle of planting alfalfa in the spring with a nurse crop because you need the tonnage that year, but at the same time, you know the competition between the nurse crop and the alfalfa will impact the stand for years to come.

These same principles apply to pastures. As of this writing, it has been over 90ºF in central Washington for a few weeks, and my cool-season grasses have slowed to a crawl. Nearly all of us experience this summer slump to some degree. Options for dealing with it include feeding hay, reducing herd size or overgrazing and dealing with the consequences later.

But there is another solution. In my case, the forage plantain that I planted into my existing pastures in the spring of 2016 is saving me right now. Plantain loves the heat and is growing well under irrigation. I’m grazing paddocks that usually aren’t grazed at all in the summer simply because I have a plant that can grow in the summer conditions.

Other possible solutions for summer slump are brassicas, chicory or the warm-season annuals like sorghum-sudan. While I got by with simply overseeding existing stands, many of these crops will do far better planted as a straight stand. At first glance, it might seem foolish to plow up a pasture and plant an annual, but in reality, even grazing operations usually have some sort of crop rotation, and these annuals can fit right in.

As a matter of fact, many experts say that a grazing-based operation should have around a third of its pasture acreage in annuals. That may be more crop rotation than many grazing operations are practicing, but taking all factors into consideration, the positive impacts of such a crop rotation usually greatly outweigh the costs and effort that it takes to do it.

In today’s reality of unpredictable weather and widely fluctuating commodity prices, we are starting to see farmers get creative with rotations that reduce the overall risk of forage production. In the Midwest, where corn silage is king, many farmers are incorporating some sorghum or sorghum-sudan in their rotation to offset the risk of drought or wet spring weather on corn silage yields.

Since these crops are planted later than corn, farmers have a great opportunity to plant a winter cereal the previous fall and harvest in the spring without feeling rushed because they have to get their corn in. This gives them three distinct harvest windows (small grain, corn silage and sorghum). Having three windows decreases the risk that all the forage harvest will be affected by weather.

In the West, where double cropping a winter cereal has been commonplace for a while, some producers are adding the twist of planting fall oats mixed with winter triticale. They get a harvest of oats late that fall and a harvest of triticale in the spring with one pass of the drill. The management can be tricky – they have learned that leaving 4 inches of stubble after the fall oat harvest is critical for the triticale to survive the winter and regrow the next spring.

As fall approaches, consider your operation and look for any small holes in your forage production calendar. Ask yourself if you are expecting forages to grow outside their optimum temperatures. An honest look will likely reveal some holes to address in any forage program. ![]()

PHOTO: Triticale is often harvested in early spring prior to corn planting to fill forage gaps in a Western forage system. Photo by Lynn Jaynes.

-

Chad Hale

- Research and Acquisitions Manager

- Western Forage Resources

- Email Chad Hale