When you finally got to your computer, it took hours to input the collected data – one hour in the field equaled three hours of data input.

Then came the advent of handheld smart devices and various starter apps that replaced that backpack full of recording paraphernalia. But there was still a problem – they didn’t work if the holder was out of cell phone range, and cattle don’t usually graze in subdivisions.

Another challenge was finding an app that could do all that graziers needed it to do – recording how extensive grazing is; measuring bare soil, plant vigor and community structure; identifying the location of range improvements; detailing the extent of weeds; determining how many animals a particular pasture will support; navigating in the field; linking digital pictures with the appropriate data; recording precipitation and weather; and logging additional written and audio notes. And any app worth investing in needed to be easy to use and generate reports that would be helpful in planning future grazing and improvements, and cut down on the paperwork required for grazing leases, financing and agency reporting.

Private company pasture apps

Christine Su has been working on the problem since 2014 as part of her master’s thesis from Stanford. She worked with over 600 farmers and ranchers, finding out what they needed pasture monitoring software to accomplish. Then she got to work. Her research led her to the innovation of PastureMap.

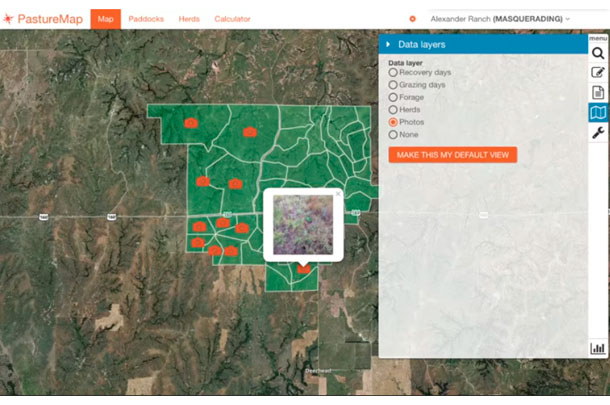

With a touch, users can create and subdivide fence lines, and calculate acres and perimeters. Grazing moves can be recorded, monitoring points can be photographed with GPS points, herd weights and average daily gains of each animal can be tracked, and everything works even without cell signal. When the user reaches cell range, the app automatically syncs with the main internet account. Data can be exported to maps or data files, interfacing with Excel. And the information can be shared with other users, so the manager can update the grazing plan from home and employees in the field can enact the grazing plans with any last minute changes.

Su says pasture apps, as with many apps, will continue to evolve and be refined based on user input and rancher requests.

University sponsored pasture app

In 2014, University of Nebraska (UNL) also released a pasture app, called GrassSnap, to monitor grass and vegetation. This app takes ranchers through monitoring steps, stamps photographs with the pasture name, GPS location and date, stores photos and comments in folders and downloads the information to a computer at a later time. Images from previous years can “overlay” a ghost image on the screen so the user can line up live images with previous images for more consistent pictures.

Bethany Johnston, UNL extension educator, says pasture monitoring is not just about the grass height, but includes other rangeland health indicators such as litter on the soil surface, vegetation types and plant condition. In a high-tech world, she finds a lot of folks who don’t consider themselves “techies.” She says, “I am not a ‘techie’ person – I have a flip phone! But I saw a need for an easier way to photo-monitor. I assisted a rancher to set up a photo-monitoring system and came every year to take pictures and collect data. The rancher told me, ‘If you didn’t come up to monitor my place, I would stop doing it.’ The rancher understood the importance of the pictures and data we were collecting, but he didn’t think he could handle a digital camera, download the pictures, input the data into Excel, etcetera. I wanted to find an easier way to photo-monitor so anyone – even someone like me who only uses technology if it saves me time or money – can monitor.”

Johnston says using GrassSnap, after the rancher takes the photo point (a picture looking out) and photo plots (pictures looking down), they can chose to enter a “Grazing Index” or “Apparent TREND Score.” The indexes and TREND score have a comment box where additional grazing information can be added. The text will be saved in the same folder as the photographs of that pasture. Precipitation records could be entered in the comment box for each pasture.

GrassSnap works without cell or wireless service. A rancher may want to use a GPS to enter locations initially. If the user is within cell service, GrassSnap enters the GPS locations automatically.

Since its 2014 launch, the app has 1,600 downloads for the Apple version. The Android version is scheduled for release by Oct. 1, 2016. Johnston says she’s been amazed at the interest in the app from states outside of Nebraska.

The GrassSnap webpage offers several documents and YouTube videos to show how to get the most from this app, available here.

Johnston says the greatest benefit of the app is “time saved.” She says, “Before GrassSnap, I monitored the pastures on our ranch. It took over three days to monitor 45 pastures. I spent eight hours downloading digital pictures, renaming them, putting the pictures and GPS and data together in folders, and it was a mind-draining, tedious process that I never wanted to do again! GrassSnap automatically names the photographs and sorts the photos and data into folders by pasture name.”

Yes, there’s no argument that learning the ins and outs of an app will take some time initially to set up and learn to operate. But you can either spend your time there or generating all the paperwork required for grazing permits and agency reporting. It’s your time – how would you rather spend it? ![]()

-

Lynn Jaynes

- Editor

- Progressive Forage

- Email Lynn Jaynes

PHOTO 1: Updated pasture apps can record more than plant and range condition, to include stocking rates, total animal units and dry matter intake (pounds). Photo by Lynn Jaynes.

PHOTO 2: "Spend less time keeping records and more time doing what you love" is the slogan for the PastureMap app, a smartphone app that helps ranchers make forage management decisions. Screenshot taken Sept. 8, 2016, at pasturemap.com