Lewis says they were sort of forced into raising alfalfa seed because conventional crops weren’t profitable on a small farm.

Lewis claims that to be in the alfalfa seed business, you have to essentially be in the leaf-cutter bee business. “Alfalfa seed is an intense crop for management. I’m not sure if I spend more time growing seed or managing leaf-cutter bees,” Lewis says.

A leaf-cutter bee has a six- to eight-week lifespan and is responsible for the pollination of alfalfa blooms. About 55 percent of the larvae emerge as females, and only female bees do the work of pollination.

Leaf-cutter bees are cavity-nesters, and to facilitate nesting, producers create “bee boards” by drilling 4- to 6-inch holes in a thick, laminated wooden block and stacking several of the boards in a “bee hut.” Much of the industry has moved toward Styrofoam blocks; however, Lewis claims better success with the wooden blocks, although they are more labor-intensive to move.

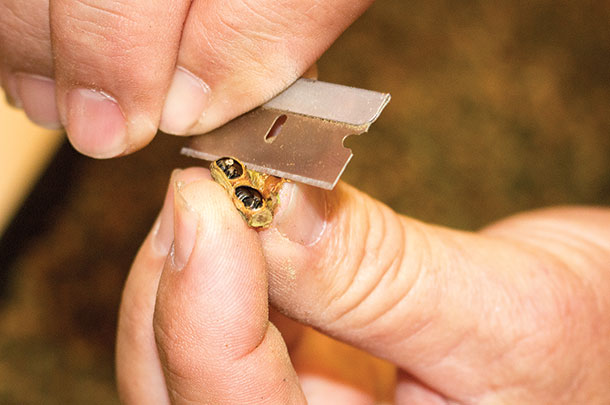

Immediately after emerging, the females construct nests or cells of cut alfalfa leaves in a drilled-out hole in a bee board, within which they will lay a single egg.

They complete the nest by including a supply of pollen for the larvae to feed on when it hatches and close the cell. The completed cell is small enough that three or so fit on your small fingernail. The bee then adds another cell and repeats the process, creating a 4- to 8-inch “straw” of stacked, connected cells.

Each September, Lewis collects the bee boards and “strips” the boards by removing the straw cells with a long-fingered instrument. He overwinters the bees in an incubator set at 40ºF. In May, before the alfalfa blooms, the incubator is heated to 83ºF to facilitate hatching. It takes 12 to 15 days in the incubator before movement of the developing larvae starts to create their own heat.

During the final seven days of the 21-day hatch, heat monitoring becomes increasingly critical. The incubator is equipped with fans and coolers to offset the rising heat.

Lewis says, “The incubator is set with temperature alarms that alert four different cell phones in the case of a heat problem, which can quickly kill the bees – literally cook them. And if you lose the bees, you lose the seed crop.”

When the larvae hatch, workers take the bees to colorful bee huts in the fields. (They assume bees can tell light, color and shape). When the ambient temperature reaches 80ºF, Lewis says the bees start pollinating, and “at 90 to 95ºF, they love to pollinate.”

The cost of bees can range from $15 to $120 per gallon, depending on availability, so management of the bees is a major investment. One problem for bees is a parasite that can develop in the incubator phase at about seven days – called Pteromalus. This is a tiny, parasitic wasp that paralyzes the prepupa and then lays eggs on it.

Pest strips in the incubator can mitigate some of the damage from this pest. The other plague is referred to as chalkbrood, a fungal disease infecting the larvae that causes death before maturity. Humidity in the incubator can also cause damage. And any one of these maladies can quickly wipe out a bee population.

Assuming the bees hatch and survive, Lewis uses 3 to 5 gallons of bees per acre, at a rate of 10,000 live bees per gallon. Lewis says some growers even use custom pollinators, moving the bee shelters from one farm to another much like custom planting or harvesting.

And we haven’t even talked about alfalfa seed yet.

Lewis says alfalfa seed establishes best with a fall planting, taking the first crop off the following fall. However, some producers use a seed-to-seed method, whereby seed is planted in the spring with the first crop harvested the same fall. The seed-to-seed method only works if the season is long, and in Wyoming that’s not always dependable.

Lewis seeds 1 pound to the acre in 20-inch rows in the fall and generally thins the alfalfa stand the first year by running a duck-foot through the field at a 45-degree angle. This essentially tears out one-third of the crop but increases production over the life of the stand. Lewis says, “You don’t want to get it so thin weeds start coming, but you don’t want it so thick that you’re combining at 0.3 miles per hour and are plugging up the combine, or you won’t get your crop in.”

Lewis contracts his seed production with Alforex, Allied and other seed companies, diversifying his risks. The average contract is three years, although they can be extended based on several factors. The alfalfa stands are rotated with barley. Lewis says it takes two years to clean up a field with barley before he can go back in with alfalfa seed, and says, “It takes that long to clean up the thistle and any old hard seed.”

Alfalfa seed production is not as water-intensive as a hay crop. Most of Lewis’ fields are irrigated with flood irrigation. Since the roots reach so deep, there are parts of the fields they don’t even have to water after establishment. Lewis says, “We just put in a pivot.

Other seed producers told us that under a pivot, alfalfa seed may not yield as well because it’s harder to raise if you don’t know what you’re doing. The first year, our pivot yielded about 200 pounds less per acre.

This year we’re fertilizing more and using foliar feed in the field, hoping to bring the yield back, but if it doesn’t come back, we’ll literally lay the gated pipe down on the ground and forget the pivot rather than take a reduction in seed yield.”

Sweet clover is one of the problems that can plague an alfalfa seed field. The first year the clover appears, it’s barely visible because it doesn’t bloom in the first year.

The second year, the clover blooms, and Lewis says, “Literally all we can do is send someone out there to chop it off and haul it out of the field. They can clean the clover seed out at the seed mill, but every time they run your seed to pull out the invasive seed, you lose some of the good seed with it. So a farmer only costs himself money if he doesn’t raise a clean crop.”

Alfalfa is also a preferred host to lygus bugs, a persistent pest that can cause widespread damage to an alfalfa seed crop before harvest. In addition, other pests move into the fields, like pea aphids, mites and others.

The chemicals to control the bugs are pest-specific, requiring producers to spray the crop as many as six to eight times before harvest in an effort to control the bugs. It’s an expensive cost of doing business. Yet at the same time, they’re trying not to kill the bees or other beneficial bugs with the pesticides.

Lewis says, “There are some beneficial bugs, and if we can get the right balance, then the good bugs help control the bad bugs.” In order to maintain bee populations, a lot of spraying has to be done at night when bees are in the shelters.

Another critical point in alfalfa seed production is when the plants are in bud or bloom stage and a hailstorm comes through. The hail can break the alfalfa stems and stop the alfalfa growth. Lewis says, “Even if some blooms continue to develop, the hail would set it back, and then we have $100,000 worth of bees ready to go into the field, but what do you do with them?”

Lewis uses a defoliant to dry down the crop when it’s ready for harvest. Using a modified combine with different screens to prevent loss, and plugging every “teeny, tiny hole” in the combine, Lewis harvests at 1 mph, generally “harvesting hard” a few hours a day from Aug. 20 to mid-September. Rain, however, can always set the harvest back.

Lewis says, “The minute it rains, seed quality goes down. Some years our tare is only 12 percent, but some years it’s as much as 35 percent.” Then seed is shipped to the seed mill in 4-by-4-by-4-foot bins for cleaning.

Lewis generally averages 950 pounds of clean seed per acre, and his best yielding crop was planted in the fall. A seed-to-seed crop can yield as much as 1,000 pounds per acre, but (like any farming enterprise) there are years when the crop produces much less – maybe only 100 pounds per acre.

The problem with a seed-to-seed crop comes when there is either a late spring or early fall that does not allow the seed to develop, so it becomes a high-risk crop.

Lewis says it’s not an easy business, but then really nothing related to agriculture is easy. He says, “If someone comes into the business, they need someone who knows the bee end of the business to help them understand the hazards. It’s too expensive to learn the lessons the hard way, like a lot of us did. Renee and I have way too much education on bees.” FG

Go to Hay in Wyoming's Big Horn Basin to watch a video on hay production in Wyoming.

PHOTO 1: Renee Lewis prepares a tray of hatched leaf-cutter bees to place in bee huts, ready for pollination. Photo courtesy of Kevin Lewis.

PHOTO 2: Kevin Lewis says alfalfa seed growing requires intense management of not only the crop, but also the leaf-cutter bees.

PHOTO 3: Kevin Lewis opens a leaf-cutter bee cell made of alfalfa leaves to demonstrate the maturing larva. Photos courtesy of Lynn Jaynes.