During the 1980s farm crisis, net farm income in Kansas was below zero for many farms. Net farm income has not approached those low levels until this past year.

The 1980s farm crisis was difficult for all farms, but many managed to survive. The lessons learned from that crisis can provide some guidance about how farms today can get through this current period of low profitability.

During the 1980s farm crisis, farmers made machinery adjustments that greatly helped their cash flow.

Machinery is one of the major expense items on a farm. Back in the late 1970s, machinery expenses ranged from 50 to 60 percent of total costs. This percentage has steadily declined so that, today, machinery expenses account for 35 to 40 percent of total costs.

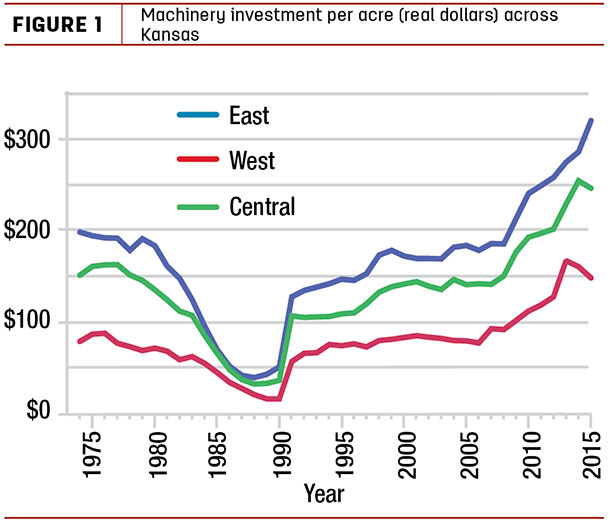

Even though machinery expense as a percentage of total costs is lower, machinery expense is still a major cost item and is one area farmers have some control over when managing expenses. This was especially true during the 1980s farm crisis, when farmers reduced their investment in machinery to 25 percent of the level before the crisis.

As shown in Figure 1, machinery investment per acre dropped to less than $50 per acre (in real, inflation-adjusted dollars). Farmers basically quit buying equipment during the 1980s farm crisis.

This reduction in equipment purchases could have been a farmer’s choice or a lender’s requirement to obtain an operating loan.

This reduction in equipment purchases could have been a farmer’s choice or a lender’s requirement to obtain an operating loan.

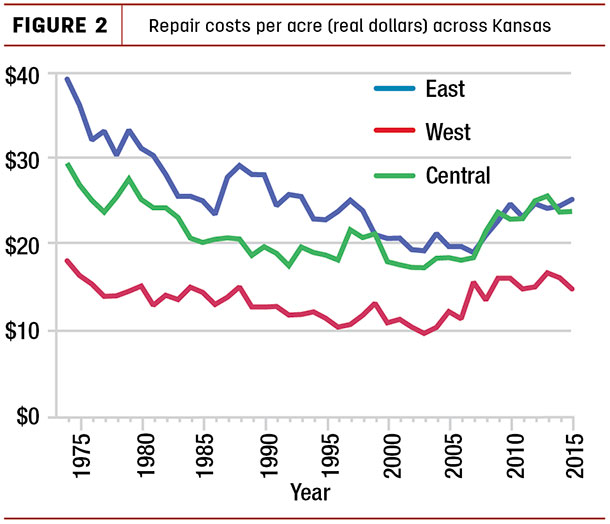

While curtailing machinery purchases may have some effect on profitability, the biggest benefit is that cash flow improves. Reducing machinery purchases results in keeping older equipment, which in turn means repairs and maintenance costs might increase.

These potential higher repair costs could negate any cash flow advantages to keeping older equipment. However, as shown in Figure 2, repair and maintenance costs actually did not increase during the 1980s farm crisis.

One possible reason was that farmers did more repair work on the farm as opposed to taking it to a dealer. Forty years ago, a farmer could probably do many repairs themselves. However, today’s machinery depends much more on electronics.

One possible reason was that farmers did more repair work on the farm as opposed to taking it to a dealer. Forty years ago, a farmer could probably do many repairs themselves. However, today’s machinery depends much more on electronics.

It is doubtful farmers could bypass dealer repairs as readily as they did during the 1980s.

During the period from 2007 to 2012 in Kansas, farmers enjoyed record levels of net farm income. Farmers took advantage of this higher income to both modernize their equipment base and to add more machinery.

The extra equipment is one reason why the repairs and maintenance costs shown in Figure 2 start to increase in 2007. Adding and modernizing equipment during more profitable years is a common strategy for farmers who own their own equipment.

An analysis of net farm income and machinery purchases shows that these have a correlation of 0.69 with no indication of any lag before farmers adjust their machinery purchases.

That is, when farmers anticipate poor profitability, they immediately start to slow down machinery purchases, and when they anticipate good profitability, they immediately start to replace machinery. Given farmers’ dislike for paying taxes, this result is not surprising.

One benefit to the purchase strategy of buying machinery in good years combined with five years of near-record farm income is that farmers now have a base of newer and perhaps more machinery than average. Thus, this machinery investment can be looked at now as a “machinery bank” that farmers can tap into.

Just like farmers did during the 1980s farm crisis, farmers today can slow down equipment purchases to improve cash flow. Farmers could reduce their machinery investment by nearly 50 percent before they will approach more historical levels of machinery investment per acre.

As farmers do slow down machinery purchases, the average age of machinery on a farm will increase. This will result in less reliability and thus more risk that field operations will not be completed in a timely fashion.

Reliability issues are probably one of the major reasons equipment is traded. Based solely on cost minimization, farmers should trade equipment whenever repair and maintenance costs start to exceed the real decline in asset value.

Typically, a cost minimization calculation results in a machine lifespan much longer than most farmers keep a machine on their farm. However, these cost minimization calculations don’t include the costs of not completing fieldwork.

Trying to quantify reliability is difficult though and may depend on other options available to a farmer. Today’s environment of low profitability will require farmers to monitor even more closely the needs to conserve cash versus the problems that an unreliable machine can cause.

Even if farmers can rely on their buildup of machinery from the recent high net farm income years to help manage machinery costs, farmers may still need to add machinery.

This could be a result of a machine becoming unreliable, or it could be from a farm trying to expand or make other changes where machinery is needed.

Due to lower projected farm profitability in the next several years, it is important for those considering machinery and equipment upgrades to think through each purchase decision carefully. Some questions to consider might be:

- Does this machinery increase efficiency or profitability on my operation?

- Can I get a better return on investment by using my capital elsewhere?

- How will this decision impact my cash flow in the next several years?

Options other than purchasing can be considered, such as leasing, renting or hiring custom work. Each of these alternatives generally tie up less working capital, so if cash flow is a concern for your operation looking forward, they might be good options.

Custom hire is a good option if a particular machine isn’t going to run across enough acres to cover your costs of ownership. Iowa State University has a useful tool to compare purchasing versus custom hire.

The decision tool can be found by visiting Iowa State University Extension and Outreach, then searching for “ownership versus custom hire” in the search box in the upper right-hand side of the screen.

By making several assumptions, you can compare the cost of owning to the cost of custom hiring and estimate the number of acres your machinery (combine, sprayer, etc.) will need to cover in order for ownership and custom hiring costs to be equal.

For machinery you already own, one option to consider is renting it out on MachineryLink. This can generate cash flow and works best for machinery, such as a combine, that may sit idle for a large portion of the year.

Sharing machinery ownership with a relative or neighbor, though not ideal, is another option since spreading your cost over more acres can lead to considerable cost savings.

Whatever decision you make regarding machinery upgrades this year, using the best information available to make an informed decision will help you navigate these less profitable times. ![]()

Greg Regier is a Kansas Farm Management Association specialist.

Gregg Ibendahl is with the department of ag economics at Kansas State Research and Extension. Email Gregg Ibendahl.